God, The Devil, and Legal Tender

Legal tender laws are the tip of an iceberg. They represent a man-made world, one in which the state, by total coercion, seeks to overthrow God's order and to replace it with a humanistic one.

- R. J. Rushdoony

Chalcedon Report #193, September 1981

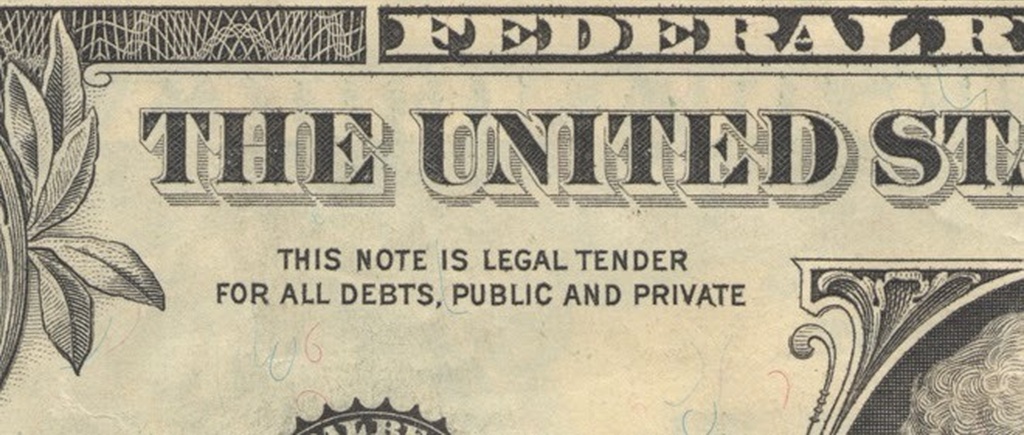

To view the idea of legal tender theologically seems strange to the modern (and humanistic) mind, but it was once an important issue in the United States. The legal tender doctrine holds that the power to define legal money belongs to the state, and the state can therefore declare what constitutes legal money for the payment of all debts, public and private.

The Rev. John Witherspoon attacked the idea very early. It was unnecessary for any state to require people to accept good money. Gold and silver were always acceptable. A legal tender law simply requires people to accept bad money, and it does take civil coercion to make bad money acceptable.

The U.S. Constitution, Article I, Section 10, states that no state can make "anything but gold and silver coin a tender in payment of debts." The Federalist, no. 44, gives us Madison's opposition to paper money. Patrick Henry opposed paper money, and Daniel Webster argued that a legal tender law is unconstitutional.

It was the lexicographer and Calvinist Noah Webster who spoke most bluntly. In 1790, Webster called a tender law "the devil." He warned, "My countrymen, the devil is among you." Of legislators who favored legal tender laws, he said that honest men should exclaim, "You are rogues, and the devil is in you!" Legal tender laws, he pointed out, were the preliminary to adulterated money, and all those who favored them were counterfeiters, deserving of the gallows, or at least the whipping post!

Legal tender laws allow good debts to be paid with bad money, so that a debt is paid with only a fraction of the value it was contracted for. The result is a form of legalized theft, Webster held. He declared in part,

"Remember that past contracts are sacred things; that legislatures have no right to interfere with them; they have no right to say that a debt shall be paid at a discount, or in any manner which the parties never intended. It is the business of justice to fulfill the intentions of parties in contracts, not to defeat them. To pay bona fide contracts for cash, in paper of little value, or in old horses, would be a dishonest attempt in an individual; but for legislatures to frame laws to support and encourage such detestable villainy is like a judge who should inscribe the arms of a rogue over the seat of justice."

Why did Webster see legal tender laws as the devil manifested in law? We cannot understand the legal revolution wrought by humanism unless we understand that fact.

For Webster and others, gold and silver represented natural and hence a God-given order of things, whereas legal tender creates an arbitrary value which can only stand with coercion. Values are God-created, not man or state created. The temptation of Satan in the beginning was to doubt God's order: "Yea, hath God said?" (Gen. 3:1). Rather, the tempter suggested a new order in which man creates his own laws, values, and morality: every man shall be his own god, determining or knowing good and evil for himself (Gen. 3:5). In such a society, the state as man incarnate can set aside God's laws and make its own laws. It can issue a legal tender law and require obedience to it. (In God's natural order, there is no need to require the use of gold and silver; they commend themselves and are in demand.)

The essence of the theocracy as Scripture's law presents it is that the state is at best minimal. A.J. Nock saw the Old Testament design as one for government, not a state. Repeatedly, God declares, This do, and live (Deut. 5:33, etc.). God's law is the way of faith and life, whereas "he that sinneth against me wrongeth his own soul: all they that hate me love death" (Prov. 8:36).

Legal tender laws are thus the tip of an iceberg. They represent a man-made world, one in which the state, by total coercion, seeks to overthrow God's order and to replace it with a humanistic one. In this new order of things, the state is the new god walking on earth, and demanding totalitarian powers and command. There is a symbolic significance that, not too many years after taking a deliberately statist course with respect to money and banking, the United States, on its dollar bills, featured a new symbol and the Latin words proclaiming the new order of the ages. That order is statist tyranny.

Legal tender laws thus cannot be viewed in isolation. Churchmen show no interest in them, although they are a clear manifestation of humanism in economics. On the other hand, economists see legal tender laws in isolation from theology, although they are a clear expression of the new established religion, humanism. Both are manifesting tunnel vision and are failing to recognize the roots of the problem.

Noah Webster saw the issue; it is a moral and theological issue. Webster saw, and again and again called, legal tender laws "the devil." He saw what these laws represented, "a deliberate act of villainy," a contempt for God's justice, the legislation of theft into law, and the deliberate conversion of the state into an instrument for theft and evil. He was right.

- R. J. Rushdoony

Rev. R.J. Rushdoony (1916–2001), was a leading theologian, church/state expert, and author of numerous works on the application of Biblical law to society. He started the Chalcedon Foundation in 1965. His Institutes of Biblical Law (1973) began the contemporary theonomy movement which posits the validity of Biblical law as God’s standard of obedience for all. He therefore saw God’s law as the basis of the modern Christian response to the cultural decline, one he attributed to the church’s false view of God’s law being opposed to His grace. This broad Christian response he described as “Christian Reconstruction.” He is credited with igniting the modern Christian school and homeschooling movements in the mid to late 20th century. He also traveled extensively lecturing and serving as an expert witness in numerous court cases regarding religious liberty. Many ministry and educational efforts that continue today, took their philosophical and Biblical roots from his lectures and books.