A Review of "The Graveyard"

Neil Gaiman’s The Graveyard Book won the highest award you can win for children’s fiction: the John Newbery Medal “for the most distinguished contribution to American literature for children.” And I’d be willing to bet that Gaiman, a Briton, is the only living author who has won the Newbery, the Nebula (for best science fiction published in the U.S.A.), and the Hugo Award (best science fiction published anywhere). He has enjoyed just about all the success that can come to an author.

- Lee Duigon

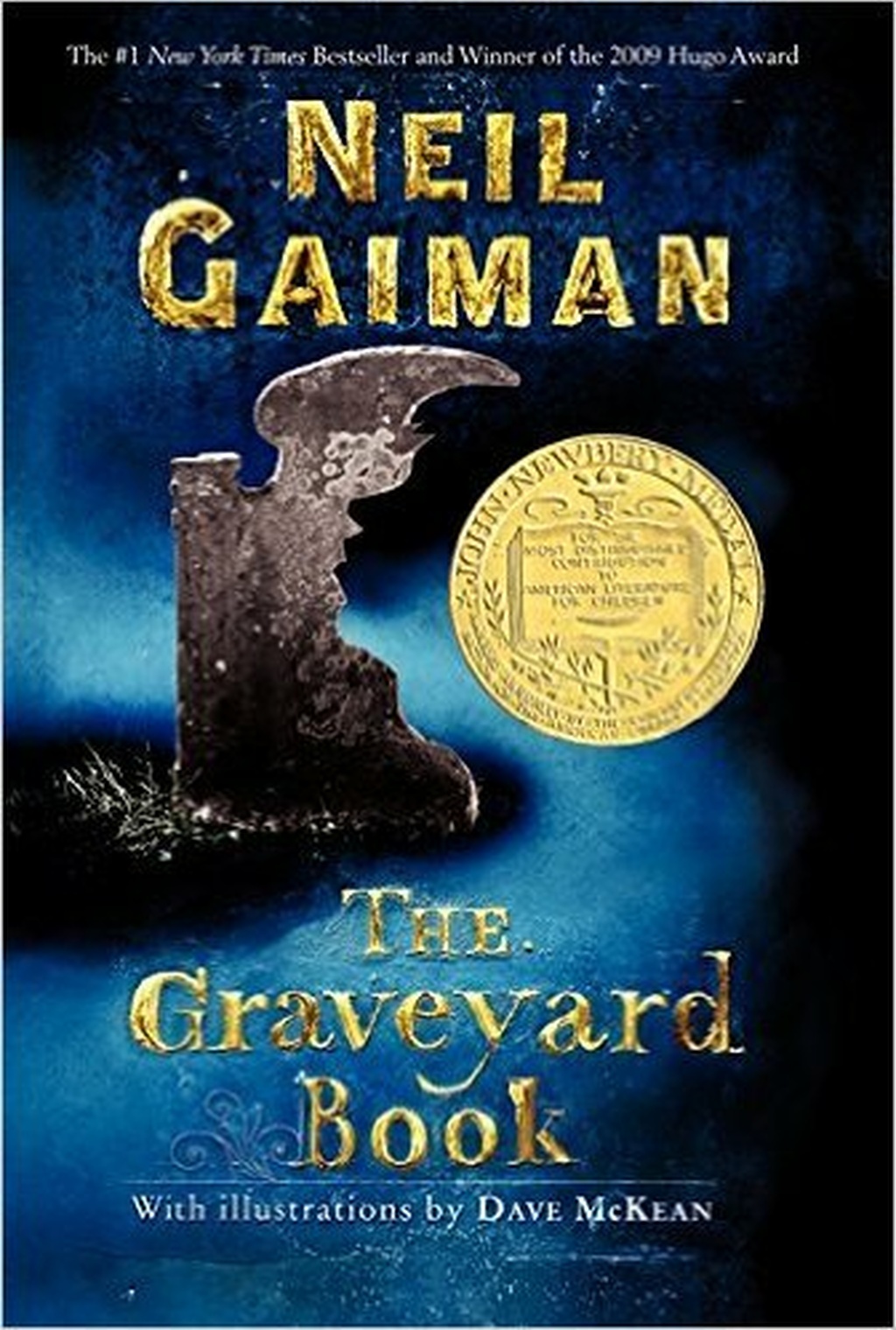

The Graveyard by Neil Gaiman (HarperCollins Children’s Books, New York: 2008)

It’s easy to bash a book because it’s full of sleaze, carries an immoral message, or is just plain idiotic—not to mention books that are all of the above.

But Neil Gaiman’s The Graveyard Book won the highest award you can win for children’s fiction: the John Newbery Medal “for the most distinguished contribution to American literature for children.” And I’d be willing to bet that Gaiman, a Briton, is the only living author who has won the Newbery, the Nebula (for best science fiction published in the U.S.A.), and the Hugo Award (best science fiction published anywhere). He has enjoyed just about all the success that can come to an author.

It’s quite a combination—a prestige book by a highly-acclaimed author. What could possibly be wrong with that? After all, aren’t we talking about a Young Adults fiction market chock-full of books about witchcraft, sexual anarchy, paganism, and open hostility to Christianity? Many awards have been won by books fitting one or more of those descriptions.

The Graveyard Book is not overtly sleazy. Amazingly, there’s no graphic sexual imagery in it at all. There is a certain amount of violence, but the author doesn’t dwell on it. There isn’t even any profanity.

No—what we have here is a cleverly-conceived and very skillfully written story: easy to see why it won a medal. This edition even includes Gaiman’s acceptance speech to the Newbery Committee, on how he came to be a writer, and to write this particular novel.

But for all its good points—and I have to admit I enjoyed the story—this is not a book that I can recommend.

Let me tell you why.

Growing Up in a Graveyard

As a young reader, an enthusiastic reader who couldn’t get enough of books, Gaiman tells us in his speech, his all-time favorite was Rudyard Kipling’s classic, The Jungle Books. He consciously patterned The Graveyard Book on these.

Just as the baby Mowgli escapes being eaten by an evil tiger, and is adopted and protected by wolves, with a black panther as his sponsor, Gaiman tells the tale of a baby boy whose family is slaughtered by a serial killer. The baby escapes by crawling into a graveyard and being adopted by ghosts, with a vampire as his sponsor and protector. The baby grows up to be a boy named “Bod”—short for “Nobody”—and he can never leave the shelter of the graveyard … because the killer is always out there, somewhere, waiting for him: waiting to claim the last of his victims, even as the tiger waited for Mowgli.

As he grows toward manhood, Bod becomes increasingly curious about the world outside the graveyard. The ghosts love him and provide him with interesting companionship, but eventually Bod can’t help taking bigger and bigger steps into the unknown, and it becomes harder and harder for Silas the vampire to protect him from the killer.

Meanwhile, Bod never runs short of interesting experiences right there in the graveyard, making unusual friends—for instance, with the ghost of an executed witch—and probing into its mysteries. His adventures in a forbidden Neolithic tomb are weird and fascinating.

All of this makes for a very cool story, with suspense piled on as Bod unknowingly draws closer and closer to his meeting with the man who killed his family.

How Clean Is “Clean”?

I can easily imagine some of you raising your eyebrows and saying, “Ghosts? Vampires? And a serial murderer! How unwholesome can you get? What kind of sleazy story is this to lay on young readers?”

If that’s your reaction, there is little risk of your Christianity being unsettled by this story.

But that’s not everyone’s reaction, is it? Even Christians in today’s America, far too many of them, are Biblically illiterate and poorly taught. They won’t think The Graveyard Book is dirty. Besides, there’s always this: “It’s only a novel/movie/TV show/whatever! Why make a big deal of it?”

Culture, Henry Van Til said, is “religion externalized.” It is the outward form taken by our beliefs—what we believe expresses itself in what we do, what we create, and how we live. We live in the culture as fish live in water, constantly gulping it. The Graveyard Book, and all the other books that are published and read, is a little piece of that culture. And we consume the culture piece by piece, seldom, or never, thinking that what we are doing, by this, is educating ourselves. We are teaching ourselves to believe in certain things and to act in certain ways.

We are teaching ourselves how to view reality.

Here, for instance, Neil Gaiman has drawn a scenario based on presuppositions that are anything but Biblical. Here we have no judgment, no salvation, no hope of resurrection. When you die, you become a ghost, existing forever in a kind of bodiless “life” confined to the graveyard in which you were buried. Whether you’ve done good or evil in your life, whether you’ve believed in Jesus Christ or not, the outcome is the same—unless, of course, you have become a vampire instead of a ghost.

But is that so terrible? The ghosts in this book love, have friendships, converse, and remain exactly the same kind of people that they were in life. Imagine an eternity of that.

Not once is God or Jesus Christ mentioned in this book. The characters simply go on being who they are, and neither Father, Son, nor Holy Ghost has any meaning for them. So here we have a suggestion—one might even call it a teaching—that you can get on all right without a Creator, a Savior, or an advocate in Heaven.

Too many people already believe this—or live as if they do.

Imagine a fourteen-year-old child who has never read the Bible, never been to church or Sunday school, never been instructed in God’s ways, and never had a conversation about any aspect of Christianity. Now we’re talking about a distressingly large portion of Mr. Gaiman’s audience.

It’s not that Gaiman has written something patently objectionable or identifiably anti-Christian. If anything, The Graveyard Book is much “cleaner” than some other award-winning Young Adults fiction. It’s not like Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials,1 a protracted atheist rant disguised as a fantasy trilogy for young readers. It’s not a blatant pitch for New Age nature worship, like Scholastic Books’ Spirit Animals series.2 Compared to these and others, Gaiman’s book might seem like a breath of fresh air.

The problem is that he’s writing out of a worldview in which no hint of God can be detected. Is this how children are brought up in Britain these days? In a culture of casual godlessness?

I’m tempted to say this work resembles The Hunger Games, which is totally devoid of even the most thoughtless reference to any kind of religious belief whatsoever. But in The Hunger Games I believed this was a purposeful omission—to what purpose, I am unable to discover—while in The Graveyard Book I found no hostility to belief in God, no rejection of Him: just a strong sense that the author never spares a thought for God at all. I realize this is a subjective impression, and may possibly be wrong; but I have limited myself to what I found between the covers of the book—as if I were a twelve-year-old boy who’d just borrowed it from the local library.

A Pitfall for the Defenseless

Our popular culture is the outward form taken by our beliefs, our worldview, what we believe to be important or unimportant: and then we turn around and consume the culture—book after book, movie after movie, passively, unthinkingly, and with all the defenselessness that such a lackadaisical approach can give us.

For many readers, The Graveyard Book will set off no warning buzzers. Once parents caught on to what Phillip Pullman was preaching to their children, they turned away from his books and the movie that was based on them died a quick death at the box office.

That’s not likely to happen with The Graveyard Book. Gaiman’s ghosts are of a pretty decent sort. The man and wife ghosts who become Bod’s surrogate parents love him and look after him as best they can, just as they would have done when they were alive. His vampire guardian is wise, caring, fatherly, and even self-sacrificing. There would seem to be nothing here that a young reader’s parents could object to.

It’s the innocuous quality of this book that makes it dangerous.

One way or another, when we read a novel, we educate ourselves. We do it without knowing that we’re doing it. We do it without thinking critically about what we’re reading. This book can do no harm to a solid, well-instructed, Biblically literate Christian who, regardless of his age, can read it critically.

It turns into a pitfall for the reader who can find nothing wrong with it.

C.S. Lewis warned his readers to make sure that what they “know” is what they really knew from personal experience, not something they “know” because they saw it in a movie or a play.3 Movies and plays are still with us, but to them we have added television, many more books and movies, video games, and an Internet notable for its complete lack of quality control. Lewis’ warning applies more to us today than it did to his 1940s audience.

For readers who have no Christian foundation, or only a vague notion of what Christianity entails, or an understanding of the gospel based not on having read it, but rather on various snippets of “sort of” Christianity that they’ve heard from this or that person, what will be the long-term effect of consuming hundreds of hours of God-free “entertainment”? Will it not become the basis for much of what they think they know? Will it not begin to shape their beliefs, their speech, and their behavior? How can it possibly fail to do those things?

Already we have a generation growing up in American who see nothing wrong with fornication of all kinds, who believe every word spoken by “scientists” and intellectuals, who sit passively in classrooms while unionized public school teachers and university professors preach to them on “gender fluidity,” “your truth and my truth,” and the Bible as only another form of hate speech. They offer no resistance to public policies that are boisterously anti-Christian, because they “know” there’s nothing wrong with any action taken in the name of “social justice.” This is the kind of thing that fills the moral vacuum left by a rejection of Christianity.

Our culture is being shaped by these beliefs, and the believers’ minds are being further shaped by the culture. Is it a vicious circle, or a kind of psychological perpetual motion machine? Either way, Christian America is the poorer for it.

So, no, despite its good qualities, I can’t endorse The Graveyard Book. To say it’s nothing but “entertainment” is to speak of it in isolation, as if the form of education it imparts were separated from the mass of an increasingly God-less popular culture.

We really must find more actively wholesome and edifying books for our young people, and ourselves, to read.

1. http://leeduigon.com/2010/11/03/satanism-for-young-readers-a-review-of-his-dark-materials/

2. See Lee Duigon, “Scholastic Seduction: The Spirit Animal Series,” Faith for All of Life, Nov./Dec. 2015, pp. 22ff.

3. C.S. Lewis, Mere Christianity, pages 109–110 in “Christian Marriage,” (HarperSan Francisco, San Francisco: 2001 edition). I have paraphrased the passage.

- Lee Duigon

Lee is the author of the Bell Mountain Series of novels and a contributing editor for our Faith for All of Life magazine. Lee provides commentary on cultural trends and relevant issues to Christians, along with providing cogent book and media reviews.

Lee has his own blog at www.leeduigon.com.