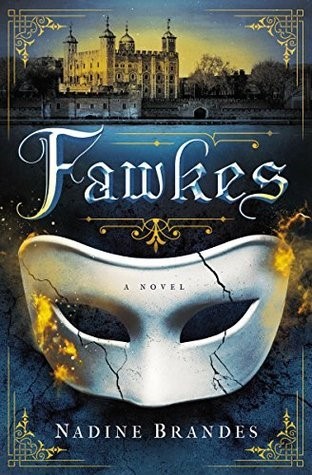

Book Review: FAWKES by Nadine Brandes

I’m always on the lookout for books suitable for Christian readers, young and old. "Fawkes", by Nadine Brandes, is directed to a teenage audience. I’m having a hard time with this review, mostly because the story is an allegory and I’m not sure I’ve correctly deciphered it.

- Lee Duigon

I’m always on the lookout for books suitable for Christian readers, young and old. Fawkes, by Nadine Brandes, is directed to a teenage audience.

I’m having a hard time with this review, mostly because the story is an allegory and I’m not sure I’ve correctly deciphered it. The author takes a fairly well-known historical incident, Guy Fawkes and the Gunpowder Plot, 1605, and twists it into an alternative history-type fantasy. We give her full marks for originality, but I’m afraid I’ll have to take off points for execution.

The Scenario

Let’s look at the story.

We’re in England, in 1604–1605. Shakespeare is still alive, James I is King of England, and the country is embroiled in violent religious controversy.

In real life, this feud was between Protestants and Catholics. In the book, Christianity is replaced by something else entirely: no Bible, no church. This gets complicated. Ms. Brandes gives us “Keepers” vs. “Igniters,” with the Igniters in power, persecuting the Keepers, and the Keepers hatch a plot to overthrow the Igniters. This much I get: the Keepers are Catholics, the Igniters are Protestants.

But instead of Christianity, we have this business of “colors” and masks. Everybody except for those in the lowest stratum of society has a mask of a particular color which gives them telekinetic power over things pertaining to that color. If your color is green, for instance, you can do magic involving plants and other green things.

Question: If everybody has such powers, why don’t they get together and clean up the city of London and the River Thames? As described by Brandes, these are highly insalubrious places. She devotes much energy to making that point. There seems to be no reason for society to tolerate such a filthy environment.

Anyway, you go to Color School and at the end of your training are supposed to “bond” with a chosen color, whereupon you receive your mask. The mask has to be handmade by your father or it won’t work.

Superior to all the other colors is White; and unlike the others, White has a personality and seeks to commune with humans. The Keepers have always sought to ban communication with the White Light, for fear it would lead to humans acquiring excessive powers which would only be abused. The Igniters want to open up communication with White so that anyone can use several different colors instead of only one. Each fears that if the other faction gets its way, it will destroy their civilization. Each is willing to take extreme measures to prevent that.

I think the White Light is supposed to be analogous to our Lord Jesus Christ. Except when the White Light communicates with the protagonist, it says things like “Okay” and makes clever little jokes.

Meanwhile, there is a Stone Plague going around that gradually turns its victims into stone, killing them. Each faction blames the other for the plague.

The Plot

Our teenage protagonist is Thomas, son of Catholic conspirator Guy Fawkes, and he goes through Color School and can’t finish because his father has failed to make him a mask. Thomas also has a touch of the plague. It seems to be arrested now, but at any time it might break out again and finish him off. So Thomas sets out for London to find his father and force him to give him a mask. And once he finds him, he winds up joining the Gunpowder Plot: to assassinate the king, blow up the house of Parliament with barrels of gunpowder smuggled into the cellar, and return a Keeper to the throne.

But as time goes on and the plot nears fruition, Thomas’ plague awakens, he is miraculously healed by the White Light, and he comes to question the morality of achieving a political objective by the expedient of mass murder. But because Christianity—or any other religion, for that matter—is not included in Ms. Brandes’ imaginary seventeenth century, we don’t know why Thomas would think any act moral or immoral. What would be the authority for thinking so? The White Light, I suppose: but most people try not to listen when the White Light speaks.

We’ve also got a love story as one of the subplots, but the less said about that, the better. In fact, we’ve got a lot of subplots, all having to do with the development of Thomas’ character. None of it seems very important, compared to blowing up Parliament.

Maybe it’s just me; but when I’m reading a fantasy set in another world, or in another time, I don’t appreciate dialogue that strays from plain English into contemporary American slang. I don’t know why so many writers do this. It looks like writing down to an audience—a form of disrespect. It also reminds the reader that he’s only reading something that somebody made up. Why the editors at Thomas Nelson didn’t correct these lapses is a mystery to me.

Why an Allegory?

The major problem here is, why is there an allegory in the first place? Certainly one could write a historical novel about the Gunpowder Plot, using the same characters and making the same points, without throwing in Keepers and Igniters, masks and colors, magical powers, and a plague that turns you into stone. I think what Ms. Brandes is trying to say is that neither Protestants nor Catholics in 1605 had Christianity down pat, and that the ends most certainly do not justify the means. But that could have been said in a straight historical novel. And maybe said better.

I am uneasy about the replacement of Christianity with what I shall call “color magic.” I have tried very hard to understand the reason for it, but if there is one, it eludes me. Also, I wonder, given the telekinetic powers available to the characters, why don’t they use those to bring the building down on their enemies?

Other Christian fantasy writers have created fantasy worlds in which the outward forms of Christianity, as we know them, don’t exist. J.R.R. Tolkien chose to animate his tales of Middle Earth with a pervasive Christian spirit and morality rather than invent analogues to the Bible and the church. C.S. Lewis put his Narnia under the lordship of Aslan the Great Lion, clearly just another way of representing Jesus Christ the King of Kings. Or you could invent scriptures and traditions and institutions for your fantasy world that are that world’s counterparts to the Christianity we know. What these writers try to do is to get the reader to look at Christian truths from a whole new vantage point. Fantasy, if so used, can be rather good at that.

But fantasy is also very, very easy to use improperly—and is often used ineptly, too. The fantasy element in Ms. Brandes’ book has no fresh insights to contribute. It does not break ground to make it more receptive to God’s Word. As embarrassing as it is for me to admit this, I don’t know what it does.

So I guess I’ll just keep looking.

- Lee Duigon

Lee is the author of the Bell Mountain Series of novels and a contributing editor for our Faith for All of Life magazine. Lee provides commentary on cultural trends and relevant issues to Christians, along with providing cogent book and media reviews.

Lee has his own blog at www.leeduigon.com.