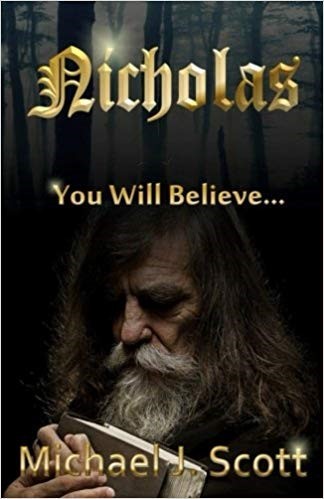

Book Review of "Nicholas" by Michael J. Scott

I wanted to review this book before I’d finished reading it. I wanted to stand up and cheer. At last—a novel fit for Christian readers (and for non-Christians, too) both young and old, and all ages in between.

- Lee Duigon

(Michael J. Scott, 2015)

For those that do not believe, no proof is sufficient. For those that do, no proof is necessary.” Nicholas to Brett Davis (p. 98)

I wanted to review this book before I’d finished reading it. I wanted to stand up and cheer. At last—a novel fit for Christian readers (and for non-Christians, too) both young and old, and all ages in between.

A hard-headed, cynical reporter, going through the motions because his newspaper has just been sold and he’ll probably be out of a job very soon, journeys to the northernmost tip of Norway to do a human interest story on an isolated monastery. And the next thing he knows, he’s interviewing—well, St. Nicholas. The real St. Nicholas, some sixteen hundred years old. How cool is that?

The man who claims to be St. Nicholas—is he crazy? And the monks who believe him—are they all crazy, too? War correspondent Brett Davis doesn’t know what to make of it.

The problem, of course, is that St. Nicholas is Santa Claus—or is he? How did St. Nicholas get to be Santa Claus?

Bit by bit, he tells us.

History and Legend

This is not Miracle on 34th Street. Nicholas does not approve of Santa Claus. For that matter, he doesn’t much like that movie, either.

What Michael Scott does is to novelize the known facts of Nicholas’ life, as recorded in church history, and then take off from there. History says the saint died in 343 A.D. But Scott’s imagination whispers, “Suppose he didn’t.”

That leaves almost seventeen hundred years to fill. It was during those years that the facts of Nicholas’ life were transmuted, by time, into the legend of Santa Claus.

All the details of the legend have their roots in history. The gift-giving, the rooftops and the chimney, the sleigh drawn by reindeer, the “elves”—monks, really—making toys in Santa’s workshop, originally located at the North Magnetic Pole, which has since moved to the Canadian Arctic—it’s not fantasy, but legend. And legend is always based, however tenuously, on fact. King Arthur, Beowulf, the heroes of the Trojan War—each is a mass of accretions on a nugget of reality.

Nicholas says God has made him immortal: because he loves God with all his heart, he lives to serve Him, and he has plenty of work to do in that service. He will be released from service, and join his loved ones in Heaven, as soon as he asks to be released. That day has not yet come.

“Truly,” writes Scott in an author’s note, “he was an amazing man, and someone I look forward to meeting in the resurrection” (p. 351).

Daring to Believe

This is what sets this book apart—the author is a passionately believing Christian with his feet anchored in the world we all know, the world which Dante called “that little threshing-floor that makes us all so fierce.” This is the world that Nicholas lives in, too. Not some pietistic spiritual pipe-dream, but right down here on the threshing-floor with the rest of us.

And the faith and the Scriptures that he has lived by, for all those years—these, too, pertain to our world. These are, indeed, the “realest” things about the real world.

How many other novelists have dared to tell you that?

At the core of this story—in fact, right in the middle of the printed book—is faith: faith in Jesus Christ as Savior, belief in whom results in forgiveness of sins and eternal life. One of Nicholas’ monks, an old man on his deathbed, is questioned as to his belief that Nicholas truly is immortal.

Brett (finding this a somewhat surreal conversation), “So he’s immortal?”

“Yes,” answers the monk, and quotes Scripture (John 11:25–26): “I am the resurrection, and the life: he that believeth in me, though he were dead, yet shall he live; and whosoever liveth and believeth in me shall never die. Believest thou this?” (p. 173)

To which the monk adds, “I tell you with assurance: Nicholas believes. That is why he lives. Rather, how he lives …”

“Believest thou this?” That is the challenge—not only to Nicholas, and even more to Brett, but also to the reader.

The two meet again at the end of the book—in New York, of all places.

Nicholas to Brett: “I have turned your world upside down … The thing is you do believe me. You know my story is true and you believe it. And that terrifies you, because if my story is true, as you know it is, then so is the story of the One Who inspires and drives me—and to Him you must give an account. You must believe in Christ. That He is the Son of God. That He lived a sinless life, died in your place, was buried, and in three days rose from the dead—and that one day He is coming to judge the living and the dead. You must believe on Him, because the eternal destiny of your soul hangs in the balance” (p. 345).

After all he’s seen and heard of this man, will the hardboiled newspaperman believe? Can he believe?

Can you?

Christian to the Core

This is not one of those “Christian books” that slaps a bit of prayer and Scripture and Jesus-talk onto what otherwise would be just another novel indistinguishable from its secular brethren. We encounter that all too often in books supposedly geared to Christian readers.

A good rule of thumb is, if the story can remain standing without the “Christian stuff,” then it isn’t really a Christian story. But if it falls apart the moment you remove the Christian elements, it is.

Michael Scott most emphatically does not slap Christianity onto his story like a fistful of refrigerator magnets. In Nicholas, Christian faith and hope and doctrine, plus the history of the fourth-century church—these are the refrigerator. The story wouldn’t last a minute without it. All the food inside would spoil. Nicholas lives and breathes Christianity. That’s why I wanted to stand up and cheer.

Add this one to your library? By all means. Let your children read it? You bet. Indeed, the original inspiration for this book was the stories Scott told his own children (Author’s Note, pp. 347–348). It’s not written down to children, but neither the prose nor the content should be too difficult for a reasonably well-educated twelve-year-old. Homeschooled kids will love it.

And so will you.

- Lee Duigon

Lee is the author of the Bell Mountain Series of novels and a contributing editor for our Faith for All of Life magazine. Lee provides commentary on cultural trends and relevant issues to Christians, along with providing cogent book and media reviews.

Lee has his own blog at www.leeduigon.com.