The Addiction Treatment That Refuses to Die (18)

This is the eighteenth—and final—article in our ongoing series covering the story of Christian physician Dr. Punyamurtula S. Kishore, whose extraordinary addiction medicine practice was destroyed by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts in September 2011. The film project inspired by this series—Hero In America—is in post-production and will soon see the light of day, covering aspects of the story only hinted at in this series. A companion book to the film, derived from the articles, is also planned.

- Martin G. Selbrede

[Note: unlike the print version of this article, this online version is unabridged.]

This is the eighteenth—and final—article in our ongoing series covering the story of Christian physician Dr. Punyamurtula S. Kishore, whose extraordinary addiction medicine practice was destroyed by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts in September 2011. The film project inspired by this series—Hero In America—is in postproduction and will soon see the light of day, covering aspects of the story only hinted at in this series. A companion book to the film, derived from the articles, is also planned.

It has been a year since the seventeenth article appeared in print. From one point of view, much has happened on the addiction treatment front ... in terms of sound and fury, signifying nothing. The same trends present five years ago have prevailed in each of the following years: higher death tolls, strident calls for action, deceitful framing of dangerous answers as “the gold standard” in treatment—we lack for none of these.

The 2018 State of the Union speech touched on opioid addiction (pretty much guaranteeing that authorities will double down on their existing failed policies). People wore purple ribbons, but because clinically proven strategies have been derailed, the ribbons are impotent gestures embodying no promise whatsoever.

We will take a slightly different tack with this final article, primarily to avoid treading old ground or stealing thunder from the documentary film project. Rather than recount the growing litany of failures, or the promising first efforts at putting Dr. Kishore’s work back on its feet, we will divide this article into three distinct sections.

The first section will deal with a specific aspect of the addiction industry’s ongoing actions to dismantle Dr. Kishore’s legacy brick by brick. Parts two and three are interviews I’ve conducted with two principals who appear in Hero In America.

Such interviews serve an important purpose. For example, the previous article in this series was based on my interview with Percy Menzies concerning the history of Vivitrol. That interview was effective in illustrating the dangers of politicized medicine.

So too here: by focusing on individuals within Dr. Kishore’s orbit but operating independently, we can see that the problems in our system are not isolated to the case of Dr. Kishore, or to Massachusetts alone. The problems we’re plagued by are systemic. The most compelling way to encounter these ugly truths is at the personal level. We will view the crisis through the eyes of protagonists who are, in effect, cobelligerents with Dr. Kishore—Christians who are dedicated to healing those still drowning in the growing addiction swamp.

First, however, we turn our attention to The Massachusetts Model of Dr. Punyamurtula S. Kishore to see what has become of it.

What’s in a Name?

Those who have followed the previous seventeen articles in this series are aware that Dr. Kishore had named his revolutionary, non-narcotic, primary care-based approach to addiction treatment “The Massachusetts Model.” He didn’t name it after himself, but after the Commonwealth[1] where it had made such powerful inroads. The work of economics professor Dr. Feler Bose (to be previewed in the movie Hero In America) demonstrates how powerful The Massachusetts Model was in its heyday as an alternative to the prevailing methadone/Suboxone-based paradigms.

If you were being treated under The Massachusetts Model, you were in the care of Dr. Kishore, and were benefiting from a system that had a clinically proven success rate (sobriety maintenance plus sobriety enhancement) of 50 percent to 60 percent (having risen from a remarkable 37 percent first clinically documented in 1994). As belabored in the previous articles, Dr. Kishore’s yardstick for success was sobriety as established by robust testing.

Conventional models using substitute narcotics use the number of patients in the treatment pool as the measure of success. If they didn’t use this sleight-of-hand, there’d be precious little success for them to measure. They have succeeded in taking sobriety off the table entirely: they win the football game by moving the goalposts, never the ball. (In the second interview below, my subject penetrates this façade in decisive, unanswerable strokes, which is likely the reason she continues to be sidelined despite her impeccable credentials and experience.)

After the destruction of Dr. Kishore’s clinical practices beginning in September 2011, the process of switching patients back to narcotic-based solutions (methadone and Suboxone) proceeded in earnest. But the choice of medications prescribed wasn’t the only thing to be switched. Even the name “Massachusetts Model” would be coopted by the narcotics-based methodologies: the exact opposite of Dr. Kishore’s approach. “Where the carcass is, there the vultures are gathered.” The name of Dr. Kishore’s non-narcotic practice was, as he sees it, picked over and hijacked by the purveyors of narcotics.

Imagine that you created The Massachusetts Model, an addiction treatment program that was achieving a 50 percent to 60 percent sobriety success rate without prescribing addictive substances. After the government takes down your program, promoting their preferred programs with only a 2 percent to 5 percent success rate, you then read that The Massachusetts Model is a Suboxone-based model developed at Boston Medical Center. Their Collaborative Care model was “subsequently dubbed the Massachusetts Model (Alford et al., 2007; Alford et al., 2011).”[2] I checked the two Alford references and found no reference to any “dubbing” with this moniker: the references provide details of the program, but don’t seem to disclose the program by that name.

Admittedly, one could argue that the apparent plagiarism is entirely unintentional, since the full names of the two models don’t actually match. But both are known and promoted by the shortened name Massachusetts Model. Which one, then, is the genuine Massachusetts Model?

More to the point: in 2011, the great successes of Dr. Kishore’s Massachusetts Model caused his clinics to thrive (a natural result of healing people from addiction so much better than other clinics). Being treated with the Massachusetts Model meant a shot at 60 percent odds of sobriety. People sought out The Massachusetts Model; they wanted Dr. Kishore’s clinics in their neighborhoods!

But now, if you seek out the Massachusetts Model, you’re getting something radically different—and far less effective. Cementing a Mercedes-Benz badge onto the hood of a Ford Pinto doesn’t turn the Pinto into a precision German sports car. Labeling a Suboxone-dependent program the “Massachusetts Model” won’t make it deliver a success rate of 50 percent to 60 percent sobriety for a year based on robust testing (let alone approaching Dr. Kishore’s sobriety enhancement standards).

Big players in the drug industry have adopted the new nomenclature. The only Massachusetts Model that exists, or ever existed so far as they’re concerned, is the narcotics-based one. The quarter-million people who Dr. Kishore treated without narcotics never enter their imagination. They’re consigned to the proverbial dust bin of history.

The essence of Suboxone-based programs was arraigned for indictment in the sixteenth article in this series, where Dr. Kishore deconstructs that paradigm point-by-point.[3] Were he given an opportunity to do so, he could just as easily deconstruct the new “Massachusetts Model” on the same basis (despite concessions to “light” primary care being incorporated into the new package).

Many hands were involved in the death of Dr. Kishore’s life-saving clinics: ignorant hands, ambitious hands, even greedy hands. Now the tombstone itself suffers the indignity of having his model’s name erased. While Dr. Kishore himself is busy working in nearby states, Massachusetts, whether by design or not, has closed the door on the founder of the original Massachusetts Model ever using that name.

Two Interviews That Matter

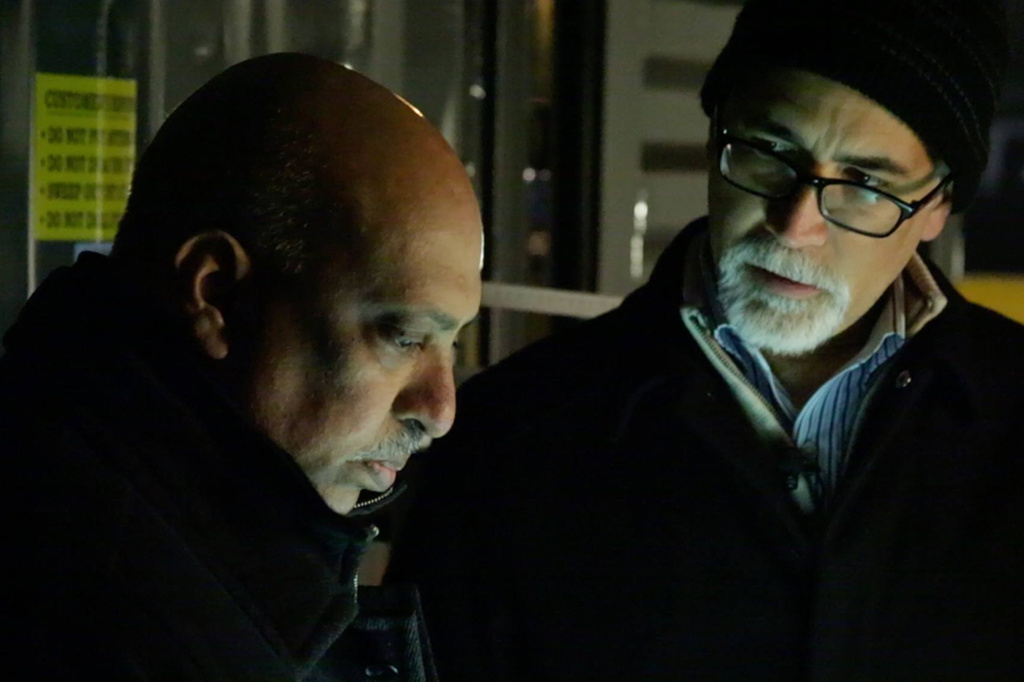

Two individuals who appear in the film Hero In America were worth separate telephone interviews with me: Rev. Steven Craft and Holly Cekala. Both of these principals approach the addiction treatment question from a Christian perspective. Such an approach can serve to filter out over-simplified reductionisms when dealing with the complexity of human nature (as seen in Rev. Craft’s case) or can provide powerful motivation to reach out and minister compassionately to those in dire need (such as in Cekala’s experience).

The respective thoughts of these two individuals, who are quite familiar with ground zero in the addiction arena, provide valuable context for the work of Dr. Kishore. We commend the following valuable interviews to the earnest reader.[4] My questions appear in bold type, with the responses following in normal type.

My Interview with Rev. Steven L. Craft

Rev. Steven Louis Craft (B.A. in Bible and Pastoral Counseling, Central Bible College; M.Div., Harvard Divinity School) is ordained as a Correctional Chaplain with the American Baptist Churches, USA and has ministered as a prison chaplain in several states. He co-authored Virtue and Vice: A Fascinating Journey into Spiritual Transformation and wrote Morality and Freedom: America’s Dynamic Duo. A former heroin addict, Rev. Craft often speaks on issues involving race, religion, politics, and culture from a Christian, Black American, and conservative perspective.

My phone interview of May 6, 2017, with Rev. Craft provides insights into the addiction crisis from someone who works sacrificially, eye-to-eye, with those affected by it.

Rev. Craft, what struck you first about the series of articles Chalcedon published about Dr. Kishore?

One of the precepts that really grabbed my attention was the idea of moral inversion, the spiritual concept of truth being turned on its head according to Isaiah 5:20. When Dr. Kishore and I were on various speaking engagements, we discussed the need for Sobriety Enhancement, where people struggling with substance abuse could learn to enjoy their sobriety! I truly thank God for you publishing those articles in Faith for All of Life magazine.

I recently saw a billboard on the New Jersey Turnpike showing a young female Caucasian heroin addict with a sign reading “WHAT IS VIVITROL”? It is absolutely amazing that the government is starting to now promote Vivitrol many years after Dr. Kishore blazed the trail for that sobriety-based solution. Hal Shurtleff has also observed the same billboards in Boston.

What is your experience working with drug addicts?

I work as a Pastoral Counselor with recovering addicts at our local church through a residential program entitled Renovation House. The program is fashioned out of the Teen Challenge Curriculum and takes approximately one year residence to successfully complete. Some of the residents finish and become success stories, while other relapse and leave prematurely. We have also experienced a few overdose deaths over the years.

What is your experience with people on methadone maintenance?

My 34-year-old daughter has a friend in Boston who has been on methadone maintenance for many years. The clinic gave her a weekend supply of the medication so that she would be able to participate in my daughter’s wedding at the time! Fortunately, she is functional and steadily employed as far as I know.

Do you have any experience with people on Suboxone-based treatment?

No, I do not.

What’s your view of Narcan, the quick-fix “life-saver” the government is promoting?

I am not a fan or promoter of this for a very simple reason. If an addict shoots heroin and overdoses when no first responders are standing at their side, the obvious result is death. This is nothing more than a secular Band-Aid, one of many so-called solutions to the drug crisis which in my opinion are too little, too late.

What’s the right solution then, Rev. Craft?

Solid detoxification needs to happen first. Primary care must follow, consisting of working with those struggling with addictions, mentoring them through programs of self-discipline, and loving them in order that they may overcome and be victorious!

In 2017 I reached out to both Gov. Paul LePage of Maine and former Governor Chris Christie of New Jersey in regard to the drug addiction crisis. Unfortunately, I did not get any response whatsoever in that regard. I have come to the conclusion that we in the Bible-believing churches must step up to the plate and disciple those who are considered “the least of these.” I came to realize that as long as the drug problem was considered an urban issue, nothing of substance would be accomplished. However, as soon as the problem spilled over into middle class communities, it became a national crisis!

Rev. Craft, can you share your personal testimony in respect to drug addiction?

Yes, I definitely will. I was a heroin addict from 1964 until 1976. I had a “hole in my soul” and used drugs to escape the inner pain! I had an awful hatred of Caucasians due to the fact that I came of age during the 1960s. I was born October 10, 1943, in New Brunswick, New Jersey. I was a black racist. I felt that white people were my problem, when in reality my problem was staring back at me in the mirror.

My cousin, Jimmy Van Dyne, who was also an addict, introduced me to narcotics. We began committing all sorts of criminal activities in order to feed our habit, which amounted to at least $100.00 per day! As a result, Jimmy died from a drug overdose in a “shooting gallery” in Harlem. So I left New York City and relocated to Los Angeles. Once there, I began using heroin again and finally got institutionalized with “temporary drug psychosis.”

That was God’s intervention in my life, and probably the best thing that ever happened to me! I submitted to God and turned my life completely over to Him through the gospel of Jesus Christ. I went into an eighteen-month residential Christian drug program known as Teen Challenge, and now can testify that I have been enjoying my sobriety and freedom from addiction bondage to this very day. I now rejoice that I have been made free through the Son of God and I travel around the world with that Good News!

Tell us about your ongoing work with your local church and ministry.

My wife and I are members of a small independent church under the supervision of Abundant Life Churches of Perth Amboy. There is a small sixteen-bed residential drug and alcohol program called Renovation House on the second floor of the church building (located at 200 Jefferson Street in Perth Amboy, New Jersey). Reverend Frank Collazo, a former addict, started the ministry in the 1970s and Pastor Paul Sears is the minister in charge at this time.

How is the Renovation House program structured?

The men in the program typically stay for anywhere between nine months to one year. Some have stayed longer, rebuilt their lives, and even go on staff to serve others that come in. Others come in, but relapse and go out because they are not committed to true change in their lives.

Renovation House teaches the Teen Challenge Program, which is Bible-based and built on consistently Christian principles. Some of the men are married with children, others are single with an average age range between twenty and fifty years old.

Two success stories come to mind. One brother in Christ finished the program, started a small roofing business, and is doing very well. He is considered a pillar in the church. Another brother, who is a preacher’s kid, is very gifted as a musician. He currently serves on the worship team as keyboard player. He is another success story.

Does Perth Amboy have “needle parks” where syringes accumulate?

I don’t know exactly where many of the addicts congregate. Many are homeless and sleep in the train station in town. So I would say there are many locations throughout the city where addicts congregate to shoot dope.

Do any other addiction ministries operate in Perth Amboy?

I am not aware of any other ministries serving addicts at this present time.

Rev. Craft, what do you see as the root of this national crisis?

My belief about drug addiction is simple. The Bible speaks about the sin of sorcery, which is pharmakeia.

I loved heroin and the high it delivered. I would do anything necessary to get my fix and avoid the withdrawal sickness that ensued if I didn’t have my daily fix of dope. I knew I was on my way to hell with my eyes wide open, but God had a plan and purpose for my life and in His great mercy He delivered me from that bondage and set me free.

When I share my testimony with others, I tell them that I believe drug addiction at its root is a spiritual problem that has physical ramifications. Dr. Kishore and I have dialogued on this issue from both a medical and spiritual perspective. We challenge our various audiences with the question, “Is drug and alcohol addiction a disease or is it a sin?” It is true that once one becomes addicted, it brings forth all kinds of disease. But addiction itself is not disease. It is sin simply because our will to choose drugs is what brings on the sin itself.

For example, one is never stigmatized for having a true disease such as cancer, but drug addiction, because of political correctness, has redefined all manner of sin to remove the stigma. This is how the addict finds solace, by saying “I have a disease” rather than by repenting and finding true deliverance from the bondage of sin.

As we know, people can kick the physical addiction simply by going through drug detox. But addiction affects body, mind, and spirit. We hear very little about the spiritual root of addiction, but we won’t get very far unless we follow the lead of John the Baptist and “cut off the sin at the root of the tree.”

Should we trust the civil government with solving this crisis?

It is very dangerous to allow the civil government to usurp the authority of the Bible-believing churches in dealing with the sin problem of addiction. The state is a false god which has only recently “discovered” (hijacked without credit) the great work Dr. Kishore was doing to truly help those struggling with the sin of addiction. Among other achievements, he combined Vivitrol for detox with primary care and spiritual counseling to achieve total sobriety enhancement.

The Wheel of Death image that Dr. Kishore developed and had you publish in Faith for all of Life vividly illustrates how elements of civil government work together at so many levels to profit financially from people’s misery.

Rev. Craft, are the churches missing the boat on this issue?

Yes, they are for sure! There is definitely a fear of addicts. The powerful stigma is very difficult to overcome, even when Christ commands us to care for “the least of these.”

Rev. Craft, in closing, have you seen other effects of stigma outside of the church?

Yes I have. I tried to get the Executive Director of a secular drug advocacy program to meet with Dr. Kishore in New York City. When she discovered some negative coverage from the media concerning his work she became very hostile. She required me to disavow my association with him or else resign from the board which she had asked me to serve on!

I tried to explain the falsehoods in the news that she had read and asked that she let him tell her his side of the story. She decided that we would part company rather than having the name of her organization “tarnished” by the likes of Dr. Kishore! I discovered that she was more interested in making a name for her organization than with working together, in a common cause, to help those struggling with alcohol and drugs.

In conclusion, I pray that my small contribution will greatly benefit your readers throughout the ministry of Chalcedon!

My Interview with Holly Cekala

Holly Cekala is a tireless advocate who has overseen the opening of two recovery centers in New Hampshire. Cekala is a certified trainer of the CCAR-Recovery Coach Academy working over the years with hundreds of Certified Peer Specialists who have graduated to placements in hospitals, prisons, and faith-based centers, in senior centers, mental health centers, homeless shelters, domestic violence centers, re-entry centers, and transitional housing.

My phone interview of July 15, 2017, with Holly can give the reader a better insight into the nature of the industry that has grown up around addiction treatment. Her experience provides a fascinating counterpoint to Rev. Craft’s and is worth digging through.

Holly, is addiction a brain disease, as former drug czar Michael Botticelli claimed?

It’s Michael Botticelli [so take it with a grain of salt].[5] Did the Surgeon General say it too? In 2015 the Surgeon General said addiction was a brain disease, and that was during Botticelli’s tenure. I don’t see that claim being backed up by any pathology reports. It’s only a condition. But a disease? I’m not sure. I’ve not seen enough documentation by any neurology team to support that claim.[6]

What is your view of the CARA Act?

CARA (the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act) was finalized towards the end of 2015, beginning of 2016, and it really dumped millions of dollars into law enforcement training, but the recovery community supported it because it was said to put treatment dollars into the community. It is the same system that is only delivering 7 percent results during this period of time, during this crisis.[7]

There actually were several pieces of legislation, including a large piece for law enforcement training. It was a bipartisan bill sponsored by Sheldon Whitehouse and Kelly Ayotte, and people initially supported it, because the recovery community was told it would be very helpful to people needing treatment. The monies would be used to teach law enforcement how to deal with mental illness and addiction in a different light. After all, mass incarceration is something that is very challenging to all taxpayers nowadays and it destroys families.

Promises notwithstanding, the millions of dollars that the CARA Act approves for treatment is delivering a 93 percent fail rate.

That massive failure rate gets glossed over, doesn’t it?

Yeah. I’ve lost a brother, a niece, a nephew, and many aunts and uncles to addiction and opiate use, so news of government action was something you wanted to celebrate. After all, they seem to be taking time to address the crisis and they’re going to spend money on it. But the system is hopelessly broken. Investing millions in a broken system is not the answer, in my opinion.

Families are so desperate for answers and ways to save their loved ones that when any hint in the media or propaganda appears concerning legislative action, they jump on it and support it. What they don’t do is read the legislation through.

Are they being emotionally manipulated?

I certainly feel like I’ve been emotionally manipulated by advocates that I’ve known for years. They all jumped on Medicaid expansion and the Affordable Care Act (ACA, popularly known as ObamaCare). All of this was under the direction of Michael Botticelli.

Of course, the state delivered a glowing report: it’s working out so well!

But others analyzed it and saw it was a mess: people are being dropped off the insurance, there are huge wait lines, and there remain large concerns.[8] Though Trump hasn’t made nice with a lot of people here, I’m thinking some reform has to be done. I support the ACA’s philosophy, but not at the expense of others!

But to increase dependence on a health care system that isn’t integrated at all makes no sense to me. It is really linked largely to this opiate crisis. If you put a large pool of high-risk people into the mix and do not change a failed system (93 percent failure rate denotes a failed system to me), what exactly are you paying for, and how are you paying for that investment in clinical care? And why is it that your primary care physician is not allowed to address addiction?

The ACA is not all about addicts, but this is the propaganda that people are pushing. There is a whole other pool of people who have been relying on Medicaid—the elderly—and elder addiction is something nobody even talks about! The elderly, for all intents and purposes, have more prescriptions than any other group of people. Addicts are usually lower on the socioeconomic scale and have more serious health problems due to reduced access to health care.

What can you tell us about the 21st Century Cures Act?

The piece that pops out to me most is that people are going to lose their informed consent.[9] They’re selling off natural resources—barrels and barrels of oil—to pay for this particular Cures act. It is preposterous. It has Big Pharma stamped all over it.[10]

I’m not a fan of this legislation. The informed consent being revoked and then being given an implant—where is the chemical slavery going to end here? Why are taxpayers spending more money to get people hooked on some other chemical? That’s not a cure. I don’t understand that. But that was never communicated. It seemed to come out of the administration on its last leg.

I’m glad research dollars are in there somewhere, but the destruction of informed consent means the patients have no recourse against a manufacturer of implants. Further, it’s a very small appropriation so far as addiction goes, so it’s like they slipped this in primarily to revoke informed consent. If you’re incarcerated and diagnosed as a substance abuse addict, they can give you the implant whether you want it or not.

This results in a snowballing effect: we’re gathering all these people with this medical condition. But where are the pathology reports? Where is the medical community? Where are the neurologists? Eighty years have gone by with clinicians who grew out of AA [Alcoholics Anonymous], a free spiritual program—I repeat, FREE—that does work for many, many people, but now we have millions and millions of dollars being pumped into this new clinical service.

If clinical care drives people into chemical slavery, I want no part of it.

How did this all unravel?

Some of the concerns that I had go back to 2012, when I sat and watched them build this Medicaid expansion[11] in Rhode Island, “I said hey, slow down, this isn’t going to work! My outcomes aren’t going to be what they used to be!” We enjoyed an 86 percent success rate using peer-based treatment: the patients went back to work, to school, and rejoined their families. When the fee per service billing was pushed on us, I saw my peers falling off and burning out very quickly. The peer-to-patient relationship changed, and I saw that it was now all about money.

People in the country want to all give back, but this particularly complex issue is one we need to look at a little bit differently. I’m not very happy with the way the prior administration had taken care of this. I saw a report not too long ago by Patrick Kennedy, who I once listened to and thought he really wants to help people, and now he’s accepting money from the very company that wants to do the implants. Wait a minute! Is this real? Have I been that naive, to think these people just want to help?

I saw these subsequent legislative acts and it seemed like they’re finally going to change things, but none of these acts fundamentally changed the way we treat this condition. I purposely use the word “condition” rather than validate the “disease” model. Addiction was defined as a disease so Medicaid could be billed for it.

There are some great clinicians out there, some great treatment programs out there, but there are a lot of programs out there that are not reimbursed through Medicaid funding. These are structured programs, faith-based programs, that might not deal directly with the condition of addiction but structure the living environment, and these are effective too. So why are we only focusing on Medication-Assisted Treatment [MAT, which involves substitute[12] narcotics like methadone and Suboxone]?

Like Dr. Kishore, you seem to have a dim view of the MAT drugs.

Those drugs were never intended to be used as maintenance drugs. They were intended as detoxification drugs so you could safely detox from the opiates you were on. “You can detox humanely,” they claimed, but why aren’t they using these drugs at the emergency rooms when people show up overdosed? That’d be the perfect time to prescribe one of them for five days. But nowadays they set the patient up for eighteen months of Suboxone, and there’s no pathology report to show that’s even the best course of action!

I see kids in their twenties and they’re put on these medication regimens that they can never get off of. Even when they say, “I want off of this,” they’re told, “You’re not ready.” Where does that end? It’s not enough that Medicaid patients and people who can’t afford insurance are put on these drugs. One of the biggest costs, even for Workers’ Comp, is Suboxone. This is what they’re pushing? It doesn’t make any sense to me. If you’re putting people all on the most expensive medication so far as insurance is concerned, how is this a stable solution?

Is there a political dimension to this?

In Rhode Island, I don’t think we have any Republicans. If we did, they weren’t very loud, you know. So I said, OK, I really wasn’t exposed to that particular political philosophy. We were just exposed to the Democrat philosophy, even as an addiction advocate. We were kind of steeped in that. So, I came to New Hampshire and wow, I met some Republicans, and they don’t know what they’re doing in respect to health. They have no idea what they’re talking about. They have never talked to the public about this, so they had very poor PR when it came to talking to the general community about recovery. How to talk about it, share their ideas, their concerns: they understood none of that.

Yet the Republicans certainly were nothing like the way they were was depicted. You know the stereotype: “Oh, Republicans are so awful, they care for nobody, blah blah blah.” I didn’t find that to be true when I came here to New Hampshire. They really did want to help people but simply didn’t know how, and now they’re dealing with this steam-rolling Affordable Care stuff. Am I just supposed to sit here and watch this happen? Or do I try to do something? If you upset the apple cart, you’re doomed to public scorn. But lots of these folks never had insurance before, so I don’t understand it.

Very few advocacy organizations have a conservative platform or exist outside a Democratic platform. Conservatives really haven’t addressed these things in their campaigns. This last primary we had every single candidate come through the centers except for a few. The only ones that didn’t come to the center were Hillary Clinton, Ben Carson, and Donald Trump. The other candidates stopped by. Jeb Bush even made a personal donation, which was pretty amazing. Carly Fiorina, Chris Christie, they all came to the recovery center, and they all had a personal experience of someone in recovery from this condition. Bernie Sanders went too.

But the conservatives have a hard time talking about it. They did not come off as empathetic. But talking with them behind closed doors, they really were empathetic. They just didn’t know how to express it. It’s going to take the entire country to sit down to have meaningful conversations to save a whole generation.

What did you see happening in New Hampshire?

Pregnant mom after pregnant mom was being put on Medicaid, so they’re then prescribed Subutex® so the child is born alive. Time and again I’d see the mother relapse repeatedly through the pregnancy and after birth—and then she’s no longer eligible for Medicaid and is moved onto other programs. How is this saving the mother or child? How is this considered investing in a solution?

Young mothers that get on methadone don’t do that well. I don’t see real people in real time in real communities do that well on methadone. I simply have not seen it. I have seen not hundreds, not thousands, but hundreds of thousands of people at some point in their life going through their addiction journey.

Could the manufacturers pull up numbers favoring their treatments?

Sure they could, but I have not seen true success. If a patient hasn’t used heroin, that’s considered a success? What about all the other things that they’re using? I picked up a young man from the hospital. He was using 190 mg of methadone and shooting up meth [methamphetamine]. He went to work every day doing these drugs. He wanted off the methadone, but you have to go to a special titration center to get off of it, and Medicaid won’t pay for getting off of methadone!

In fact, you have to have a special protocol for getting off methadone, because you have to go against the doctor’s advice, and typically doctors never say you’re ready to get off of it. You’re never going down in dose: they keep kicking the methadone dose up. “You mean I’m not high enough to not want to be high?” The system is incoherent. It is easier to kick the dose of methadone up than to reduce it. Ironically, if you don’t have the money to pay for it, you’ll be down-dosed in five days, but if you have the money for it, the dosage goes up. And it goes up continually. I don’t see how that is curative.

My view is very different. Whatever it takes to get your life and your family back, we want you to engage in that. Is your life fulfilled if it’s depending on another chemical that is being prescribed?

What about Suboxone?

When Suboxone came out, we were told it’s a great drug for detox. Detox in five days or maybe seven days. That was a pretext. Nowadays those prescriptions run for eighteen months at $1,800 per month at cost.[13] How is that supposed to be saving the taxpayers money? It doesn’t add up to me.

You were on the ground floor of recent developments, yes?

In 2012 I was invited to the White House to go and watch them build this whole thing, and I was thrown in the mix with all these advocates. We had lost two hundred Rhode Islanders in one year to overdoses. And these advocates came out and said, The ACA will help you guys, we’re really fighting for you guys, and at the time we were so desperate that we became wrapped up in it. I thought, maybe they are being honest and legitimate and this time they’re going to help it.

Now I’ve watched two different states gravitate toward this Medicaid expansion model over the last several years and I’m disappointed and filled with regret that I ever promoted it. And people will be surprised to hear that. I really thought they were earnestly trying to help people, and then I heard these things about expanded medication, and I thought, what is this? You’re just taking the corner away from the local drug dealer?

How can you be considered okay if you’re nodding off when you’re putting your child on a bus? Is that a cure? Is that not devastating to that family? I have a hard time accepting it. And you know, it’s what you call the elephant in the room when you go into recovery modality or community with other advocates. You are required to accept the enforced orthodoxy that everyone is in recovery, that they’re all doing well, and that abstinence isn’t the only way. I’m not here to judge anyone, I have only one judge, God, and I judge no one else. But I think people are being sold a bill of goods that’s doing more harm than good.

In what ways is the current orthodoxy incoherent?

If addiction is a brain disease, why aren’t they going to see a neurologist? Why is there no neurological treatment for them? The medical providers have long since left the building because there was no reimbursement rate for this particular “disease,” so doctors spent no time dealing with it.

Now that this waiver thing is in place, they’re all scrambling to treat those “addicts,” even at terrible reimbursement rates. What does that say for how we’re dealing with this? You can’t incarcerate everyone, so you’re going to put chemical bonds/chains on them? Is that not just the same thing? Enslavement? You know? If we’re supposed to be a country of free people, free-thinking people, how can you have free thought if you’re dependent on chemicals?

That I’m the only one talking about this makes me feel like a tad bit radical, because none of the other recovery advocates will talk like this. Those few who do are typically centered in faith-based programs. Those are spiritual, abstinence-based programs that have been proven to be very successful, like Teen Challenge, or Living with Grace, and things of that nature. For years those programs didn’t get any reimbursement from any insurance company, though they were saving the insurance companies hundreds of thousands of dollars.

What was your response to all this?

I didn’t want to accept Medicaid on a pay-per-service scale when I came to New Hampshire. In Rhode Island I watched it not be very successful. I watched it dwindle. When I came to New Hampshire and we set up the centers, we came up with a model that did not need to seek Medicaid fee-for-service reimbursement. And that was not received very well by those who supported the Affordable Care Act.

It was truly a big battle when I arrived here in 2015, and they’re now certifying peers. I gave clear warning about using certification for peers, because you’re essentially certifying lived experience, and quite frankly I’m not sure that’s the academically correct way to approach it.

And how do you pay for somebody’s empathy, kindness, or experience? It doesn’t make sense to me. It’s very strange to me to have to be teaching a class how to be empathetic and nonjudgmental to people who are struggling, but here I am teaching people how to be their brother’s keeper. So I stepped back from all of that so I could rethink all of this for myself.

Am I the only person out here who thinks that giving people who have money insurance is a bad thing? But in my circle people say, how can you be against that? There’s just so much animosity out there, you can’t have a good solid debate or discussion without people imputing motives. They use people’s heartstrings to keep the system going. But I know the system doesn’t work.

The politicians keep pushing for the system to remain the same way, and pushing a 93 percent fail rate isn’t going to help—it’s not metaphysically possible. If there aren’t huge systematic changes in mental health and addiction care, you can’t possibly begin to scratch the surface in changing the outcomes.

As you describe it, the situation looks grim.

I don’t know where to turn, because there’s no advocacy organization willing to discuss this in a reasonable light. There’s no middle ground between ACA all in, or kill the ACA. My God is a loving God, and I know something good is going to happen, and I think it’s important that people speak up if they have information to share. My mom told me, “You have to speak the truth even if your voice shakes.” Even on my own Facebook page there are people who are desperate to keep ACA intact. But they don’t understand the underlying issues that make it such a horrendous bill.

I have people just drop me or whatever, but God won’t drop me. I have to tell the truth. The reimbursement rates are horrifying. The insurances on the exchange are awful. Minuteman Health on the New Hampshire exchange was supposed to insure 10,000 people but they could barely keep their doors open. Those clinical teams work hard to try and help people, they really do, and they should have been paid all along. But now they’re desperate. They figure parity is in the ACA, but won’t be in the replacement act.

If you’re going to have insurance for people who need it, of course treatment has to be in there, but to what end? Where are the successes? How do you hold the providers accountable for that? “Oh, you can’t hold people accountable—it’s a disease!” How do you hold a provider accountable? With no after-care, no recovery house, no life skills after-treatment occurs, you’ll simply perpetuate that 7 percent “success” rate. How are they protecting that investment? Are they going to appropriate money for recovery houses? They just keep saying, “This is going to help people.” That now seems like an empty talking point to me.

I went to treatment twenty-five times before I found recovery. Twenty-five times! And that’s not what got me into recovery. And many of the friends I had went into recovery repeatedly, but only found recovery when they explored the spiritual dimension, acquired life skills, and got off the treadmill. And I don’t see any of this changing with the ACA act. I see nothing better than a 7 percent.

I dropped $65,000 on an education to become a clinician, only to find out I don’t want to work in that field because the system is so broken. We have to find another way to approach this. Something better than taking away informed consent and slipping people an implant—that’s not the way to deal with it. We’ve been sold a bill of goods that will not hit the mark.

I still sit here as a person in recovery and I cannot afford insurance. My deductible would be $7,000. So, I pay the $350 fine on my taxes. I don’t know how THAT is supposed to be helpful.

How did the current crisis start?

This goes back to years and years ago when they deinstitutionalized all the state hospitals, which were atrocious anyway. Then the homeless population got bigger, and that group was fraught with addiction issues. Did the country ever look to the communities of faith for help? No, they didn’t. No matter what religion you are from, Jewish, Christian, Buddhist, we all want humanity to do better, but they never embraced the faith community to say, hey, we have a problem with spirit here.

We don’t stick together as families anymore. We have broken home after broken home. We have people who make babies but don’t want to be a father. “It’s not a moral failing, addiction ... but a lot of moral failings lead to addiction.”

I was spiritually bankrupt when I was using alcohol and cocaine. Spiritually bankrupt. Is there a way to find a bridge? Years ago people went to church when they had marital problems. They went to their pastors when they were spiritually bankrupt. I had bad experiences in my church youth group, and that pushed me away from my God for a while, but thankfully I found my way back to Him. These experiences push people away from God, and I find this heartbreaking because there is joy in faith, and there are a lot of people have no more joy in their life.

What things need to change, then?

I watch time and time again men coming out of prison, and they can’t be hired at a job to take care of their families. Once they’re arrested, it’s a life sentence. All they want is to take care of their families, and this, they’re denied.

We need programs that teach independence, not dependence. When do you come off the treatment? When is that program going to find you independence? I see people celebrating that they have low-income housing. They celebrate that they’ve become completely dependent. I don’t think that’s very American. People are being sold this bill of dependence. And who benefits from that? Unless you’re a pharmaceutical company, you don’t benefit from it.

A true Christian is kind to other humans. We treat people as we would want to be treated. We love people and we don’t judge. That’s a true Christian value to me. You help where you can. So the mission was to help people any way we could so they’d realize that having a life of independence and joy is where they want to be.

And it’s been quite a decade for me, learning all these things! [Holly laughs at the thought.] And it came down to me saying to myself, “You know, what you’re saying, Holly, is definitely not popular, but if you’re speaking the truth, you simply have to speak it.” Conservatives have this awful public image presence with the lower socioeconomic community and have been unable to organize or talk to them. This represents a major communication glitch to me. People don’t understand what it is to be free. And that is concerning to me.

Let’s walk through some of the status quo tools now in use. What about methadone?

Methadone? It can be really effective for people who have comorbid conditions (serious accidents who need pain medication). For them it can be a very effective protocol. I would not recommend it to the twenty-year-old that is physically able, or to a younger person who could fully recover without it. But time and time again, I see exactly that happening. What are we looking to build? What kind of generation will we build on methadone? I’m not against medication, but mainstreaming chemical slavery is not a good thing either.

And Suboxone?

I think Suboxone could work as a detoxification drug in a five to seven day protocol. People should not have to withdraw in such pain that they go through hell. That is terrible. It could be effective if used the way researchers intended it in the first place. But now Suboxone has snowballed into a money grab.

And the new “panacea,” Narcan?

Well, Narcan was effective until the onset of fentanyl and carfentanyl. I advocated for Narcan for the Good Samaritan law for loved ones and recovery houses to have it. From 2012 to 2015 I saw it save many lives (because relapses happen). But now it’s becoming less and less effective. Why? The way it’s administered? Now we’re at the point that we’re saying, go into a public place and use your drug safely? Where does this trend end?

Clearly, I don’t want people to die if there is an antidote. I want people to have access to Narcan. But, where is the boundary? I protested when they killed the Good Samaritan law in Rhode Island (by letting it sunset). People could have been charged [with a crime] for giving Narcan to another person in need. But Narcan is typically prescribed to you, and you’re not using it for yourself, but you give it to somebody else who is in overdose and dying.

People could be saved to embrace a life of recovery (which would be optimal). That doesn’t always happen, but it’s optimal. In that sense, Narcan is no different than a defibrillator. It’s just a tool in a medical toolbox and gives the patient an opportunity to make the changes to get to recovery. But nowadays it is administered but the second, third, and fourth steps are never taken to get them into recovery.

The police are not paid to give emergency services. It’s EMTs and firefighters who are trained to use Narcan, and who are supposed to use it. The police are supposed to be upholding the law.

What’s your opinion about the sheriff in Butler County who refuses to issue Narcan to his officers?

Do we have a duty to save lives where we can? Absolutely. But is it everybody’s duty? I don’t know. If you give somebody Narcan and don’t take them to follow-up care, you’re doing them a disservice. Optimal means going straight to the hospital to begin detox, but people have the choice to stay strung out on drugs. That’s the condition they’ve trained their brain to be in. Craving withdrawal is pretty awful. But at what point do these people accept accountability for their lives? I don’t know. I don’t have the answers to that.

If you’re defibrillated, you go to the hospital and get care. They don’t just defibrillate you and let you go to sit on a couch and eat potato chips. The clinical world and the addiction world live on two different mountains and there’s a huge valley between them. We’re pretty smart people in this country and we have yet to come up with viable medical solutions that people can live with viably, live with successfully? That seems very strange to me. The conversation needs to change.

But these status quo approaches are still being aggressively pushed.

I’m not buying it anymore, the claims that “they need A, they need B.” I say, show me the research, show me the pathology reports, the neurology reports ... then I’ll buy it. But right now it seems like a huge money grab to me. It’s seems awful to say, but it’s true.

I’ve seen people struggle to keep recovery houses open, but there are hundreds of thousands of people who have recovered through them. “Where’s the reimbursement?” is a greed-filled motive, and that has to change, because we’re losing a whole generation to chemical slavery. That’s not enough to start a conversation that’s different? It should be. It should be.

Do you see any success stories out there?

The successes? As always, the twelve steps always produce successes. When people get their lives back, have love and support around them, it’s tremendously successful. When you bring a community together and expose people to compassion while they mend their soul and body ... that’s imperative. Use peer support where it can bolster success tremendously.

But do I think professionalizing peer support and stamping it with a certificate, saying You’re a good peer today but tomorrow you’re not due to a confidentiality slip ... I don’t think it has to be like that. People are people, and people make mistakes. So I don’t know if I need a certificate to love my fellow human, but that’s the way it’s going now, and you have to pay for that certificate.

If you have a gathering of people with the same understanding, that kind of support system pumps out success after success after success. General health is being bolstered. All that happens because a community heals together. You should not disallow the community the opportunity to do that.

And where do you stand in the midst of all this?

Quite frankly, I’m not trying to be popular. I’m trying to help people survive. I don’t have anything paying my way to say it that way. I’m not being paid by this provider, or that pharmaceutical company. I’m not being paid by anybody. I’m Holly Cekala, John Q. Public, not being paid by anybody. I’ve seen hundreds of thousands of people get their lives back, and that was not attributable to some pharmaceutical company. When is the conversation going to be about THAT? When are we going to talk about THOSE things, and teaching people how to embrace their freedoms? I hope that comes some day.

What do you see as the pitfalls of Medicaid?

The big one is that the treatment center doesn’t want to accept the Medicaid payments because they’re so low. Betty Ford charges $30,000 per month for a treatment regimen. Some treatment providers charge $3,600 up to $4,200 per week.

Under Medicaid you have to accept $3,200/month. To accept this, you have to have less-educated staff. Where is the scientific basis for that? What are you getting for that money? How do you navigate this complicated system? Do I go to Betty Ford or go the cheap way and pay $3,600/week? How is John Q. Public supposed to figure out how to get the best care you can get? There’s no transparency. And what does a treatment center actually give someone? What are you connecting people with?

If my job as a clinician is to connect people to a free program, why don’t they connect them to a free program in the first place? That doesn’t make sense to me. We have a whole generation in crisis here. It’s no time to multiply paperwork. So I don’t follow that methodology.

Like Dr. Kishore, you’re no stranger to major controversy.

I had complaints lodged against me by disgruntled employees and New Hampshire public radio blew it up to where were all sorts of things not right with me. That gave the state leverage to push the organization to bill Medicaid. That’s because the state hierarchy is loaded with people who follow the Democratic ACA propaganda, big government, etc. It’s all of a piece.

I had a couple of employees lodge a complaint against my license. I’m a licensed alcohol and drug counselor, even though I’ve never had a patient or client the entire time I had the license. I don’t believe you can be effective without creating a personal relationship or friendship with somebody.

License, yes, I paid a lot of money to go to school to get it. So I’m not worried about it. Did I leave the organization as a result? Sure I did. I don’t want a couple of complaints against me to stop the organization from doing what it needed to do. “We’re going to suspend the funding until we figure this out,” they said, but the investigation was over in two days. But then they said that to turn the funding back on, the organization would have to bill Medicaid. And at that point I said, okay, I’m done.

The centers don’t take that much money. Why they would want to push fee-for-service onto people? The only reason is to further the Affordable Care Act! Fine, but that’s not what I want to do.

So at the height of my career, I realized I don’t want to do this. I’d rather work with the faith-based community and do my best to save the ones I can. It took me a couple of weeks to process through this, but that’s the way I feel.

One of the complaints was that I offered a young mom and child a place to stay. And I had offered them a place to stay. And the authorities said, “That’s not good for your license,” but I answered, “That’s not good for my faith, not to offer this mother and child a place to rest their head while they’re figuring things out, so if it’s between my faith and my license, I choose my God.” That’s what people do when they have conviction. The organization even retained an attorney for me since they didn’t feel I did anything wrong.

I’ve been very vocal about a lot of things, like Dr. Kishore, you know. When you’re vocal about things that are not public mainstream, things like this happen. I take it one day at a time. But to choose between my faith and that license, they can have the license, because I want to go to heaven.

I still get countless phone calls a week from people who are wondering what they can do. You should connect with the God of your understanding, and guess what, folks: that’s free. I don’t think the medical spirit will heal a broken spirit any time soon.[14] They can have at it while they try to create their solutions, but I’m going to live in my own solution while they figure that out. Now I’m investing my time in my farm, and I definitely offer folks advice as a friend every single day. I try to support people that I love that are struggling. I’m going to continue to do that. And I don’t think a license is going to make or break me.

Is there a connection between your story and Dr. Kishore’s story?

When I heard the timeline for Dr. Kishore, I gave him a call. “Hey, I want to hear your story,” I said. The timeline for him perfectly aligned with all the ACA imposition and the push for this chemical slavery. This guy, Kishore, had actual results, scientific reports, urine tests, blood tests, etc. He had the actual scientific evidence that what he was doing in his practice was working. He circumvented the treatment system, and that is why this happened to him. You circumvent the billion-dollar clinical care system and boom: you’ve got a problem.

I designed and opened a place call Amber’s Place, a recovery respite, with people in serious need with no place to go. We circumvented the detox—people were waiting for detox for up to three to six weeks and they were fine, they didn’t need it anymore and in fact didn’t even meet the criteria [for detox at that point] anymore. It worked for four hundred people, but they shut that program down on us. Which is no surprise to me, because you can’t circumvent money like that and expect there to be no retaliation from the people making that money. They had a lot riding on that in Massachusetts, and Michael Botticelli and the Obama Administration had a lot riding on that plan, so I don’t doubt the Kishore story ... not even a bit. The timeline is uncanny for the Kishore timeframe. Uncanny. They did that to him to perpetuate the generation of more chemical slaves.

[1] https://modelmassachusetts.wordpress.com/2013/09/10/national-models-of-addiction-treatment/amp/

[2] www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4682362/#R1

[3] https://chalcedon.edu/magazine/dr-kishore-breaks-the-back-of-fake-news-addiction

[4] After reviewing his original interview, Rev. Craft decided that several adjustments were in order to avoid burning bridges unnecessarily. Therefore, some of the most incisive aspects of the original had to be scaled back, not because the data was untrue, but because disclosure could prove inadvertently harmful in ways not initially contemplated during the interview process. While we would have wished to publish the original interview, we understand the wisdom behind Rev. Craft’s requested edits.

[6] http://www.thecleanslate.org/myths/addiction-is-not-a-brain-disease-it-is-a-choice/

[8] https://www.thebalance.com/what-is-wrong-with-obamacare-3306076

[9] http://www.thelancet.com/pdfs/journals/lancet/PIIS0140-6736(09)61812-2.pdf

[10] https://articles.mercola.com/sites/articles/archive/2016/07/13/21st-century-cures-act.aspx

[12] https://www.motherjones.com/politics/2017/05/tom-price-opioid-addiction-treament/

[13] Dr. Kishore notes that the current costs for the medication (by itself) appear to be lower than Holly has suggested. See https://www.eveningpsychiatrist.com/suboxone/cost-of-suboxone-treatment/

[14] ttp://m.recoveryonpurpose.com/upload/Role%20of%20Spirituality%20in%20the%20Recovery%20Process.pdf

- Martin G. Selbrede

Martin is the senior researcher for Chalcedon’s ongoing work of Christian scholarship, along with being the senior editor for Chalcedon’s publications, Arise & Build and The Chalcedon Report. He is considered a foremost expert in the thinking of R.J. Rushdoony. A sought-after speaker, Martin travels extensively and lectures on behalf of Christian Reconstruction and the Chalcedon Foundation. He is also an accomplished musician and composer.