The Biblical Doctrine of Government

One of the most revealing and deadly linguistic errors of our time is the equation of the word "government" with "state." When the average person, and indeed almost every man, hears references to government, he immediately thinks of the state.

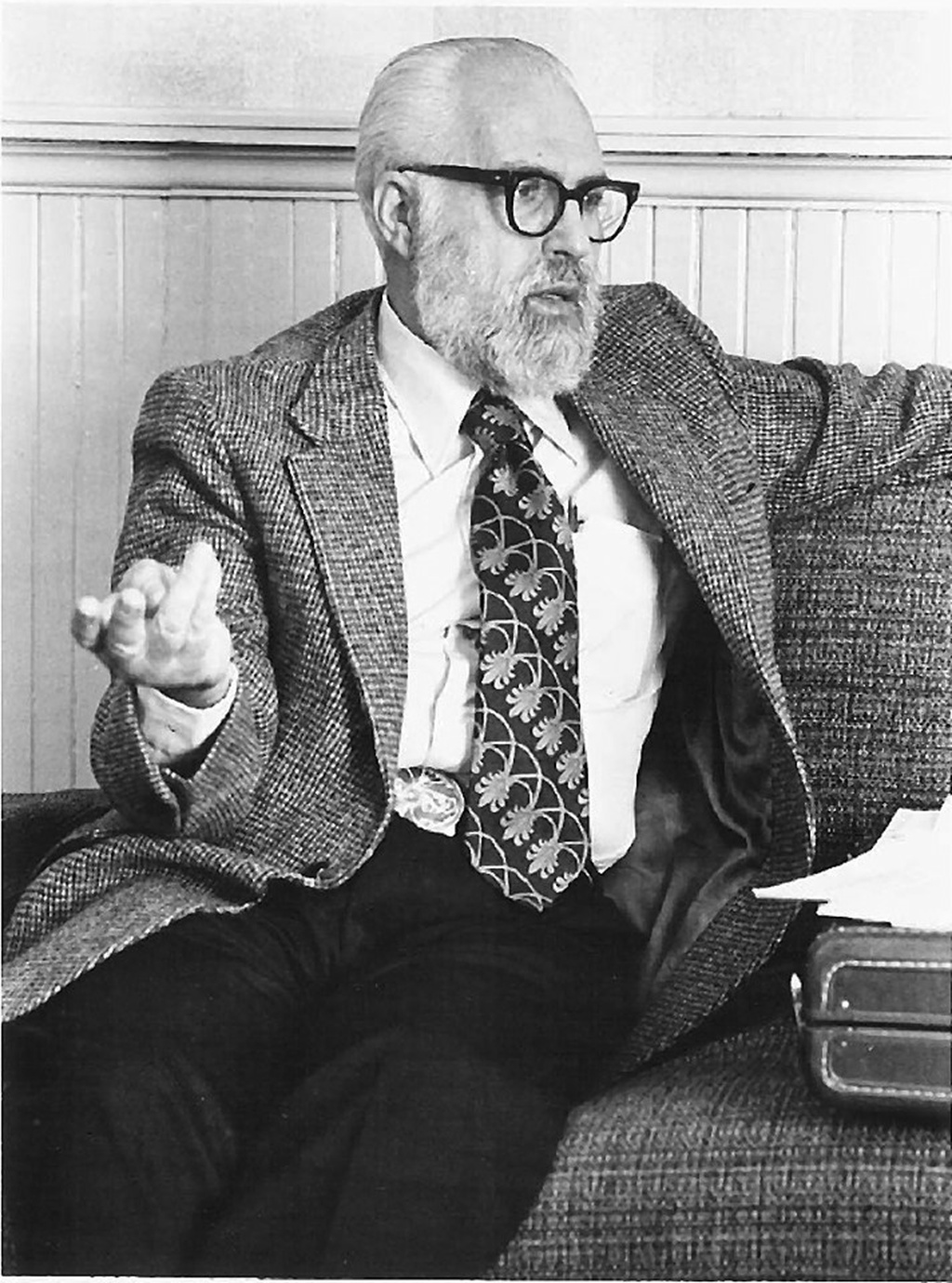

- R. J. Rushdoony

One of the most revealing and deadly linguistic errors of our time is the equation of the word "government" with "state." When the average person, and indeed almost every man, hears references to government, he immediately thinks of the state. This usage is a relatively modern one. There was a time when, in common usage, especially among the Puritans, the term for the state was "civil government." Government in itself was a much broader concept.

Government meant, first of all, the self-government of the Christian man. The basic government is self-government, and only the Christian man is truly free and, hence, able properly to exercise self-government. A free social order rests on the premise that self-government is the basic government in the human order, and that any weakening of or decline in self-government means a decline in responsibility and the rise of tyranny and slavery.

Second, next to self-government is another basic form of government, the family. The family is man's first state, church, and school. It is the institution which provides the basic structure of his existence and most governs his activities. Man is reared in a family and then establishes a family, passing from the governed to the governing in a framework which extensively and profoundly shapes his concept of himself and of life in general.

Third, the church is a government and an important one, not only in its exercise of discipline but in its religious and moral influence on the minds of men. Even men outside the church are extensively governed in each era, even if only in a negative sense, by the stand of the church. The failure of the church to provide Biblical government has deadly repercussions on a culture.

Fourth, the school is a government, and a very important one. The desire of statists to control education rests on the knowledge of the school's significant part in the government of man. For formal education to be surrendered to the state is thus a basic surrender of man's self-government.

Fifth, a man's vocation, his business, work, profession, or calling, is an important government. A man is governed by the conditions of his vocation or work. In terms of it, he will educate himself, uproot his family and travel to another community, spend most of his waking hours in its service, and continually work therein to attain greater mastery and advancement. Vocations are both areas of government over man and, at the same time, a central area of self-government.

Sixth, private associations are important forms of government. These can include a man's neighborhood, his friends, voluntary organizations, strangers he must meet daily, and other like associations. A man dresses, speaks, thinks, and acts in an awareness of these associations, with a desire to be congenial, to further a given faith or cause, or to enhance his social status. These associations have a major governing influence on man, but they can also be means and areas whereby he exercises his government over others, influencing or directing them.

Seventh, another area of government is civil government, or the state. The state is thus one government among many, and to make the state equivalent to government per se is destructive of liberty and of life. The governmental area of the state must be strictly limited lest all government be destroyed by the tyranny of one realm. The issue in the persecution of the early church was the resistance of the Christians to the totalitarian claims of the state. The Christians were asked to sacrifice to the genius of the emperor, i.e., to offer incense to him. This, in its earlier forms, was not a recognition of the deity of the emperor, because only the dead emperor was deified upon approval of the senate. It was a recognition that the state, in the person of the emperor, was the mediating and governing institution between the gods and men, and that all life and government was under the jurisdiction of the state. Religious liberty was available to the church upon the recognition of that premise. The Roman Empire, in other words, like the modern state, assumed that it had the right to deny or to grant religious liberty because religion, like every other sphere of human activity, was a department under the state. The church denied this. Christians defended themselves as the most law-abiding citizens and subjects of the Empire, ever faithful in prayer for those in authority, but they denied the right of the state to govern the church. The church, directly under God, cannot submit itself to any government other than that of Jesus Christ. This was the issue.

Abuses of order within the church are no more under the government of the state than abuses within the state are under the government of the church, and the same is true of every other realm of government-family, church, school, business, and the like. Reformed theologians restricted the right of rebellion against an unjust order within the state to a legitimate order within that state, i.e., to other civil magistrates, who in the name of the law moved to correct the abuses of civil order.

The various spheres are interlocking and interdependent and yet independent. Thus, Deuteronomy 21:18-21 deals with the death penalty for a juvenile delinquent. The parents do not have the power of the sword, i.e., of capital punishment. Upon reporting the incorrigible nature of their son to the city elders, the parents carried their governmental authority to its limits. The elders, upon confirmation of the charges, then assumed their jurisdiction, capital punishment for what was now, upon report, a civil offense. Clearly, the various spheres do not exist in a vacuum; they are interlocking, but the integrity of each is nonetheless real.

- R. J. Rushdoony

Rev. R.J. Rushdoony (1916–2001), was a leading theologian, church/state expert, and author of numerous works on the application of Biblical law to society. He started the Chalcedon Foundation in 1965. His Institutes of Biblical Law (1973) began the contemporary theonomy movement which posits the validity of Biblical law as God’s standard of obedience for all. He therefore saw God’s law as the basis of the modern Christian response to the cultural decline, one he attributed to the church’s false view of God’s law being opposed to His grace. This broad Christian response he described as “Christian Reconstruction.” He is credited with igniting the modern Christian school and homeschooling movements in the mid to late 20th century. He also traveled extensively lecturing and serving as an expert witness in numerous court cases regarding religious liberty. Many ministry and educational efforts that continue today, took their philosophical and Biblical roots from his lectures and books.