Clavius, a Roman military tribune serving in Judea at the time of Christ, dreams of “a day without death.” But what he ultimately finds is very much more.

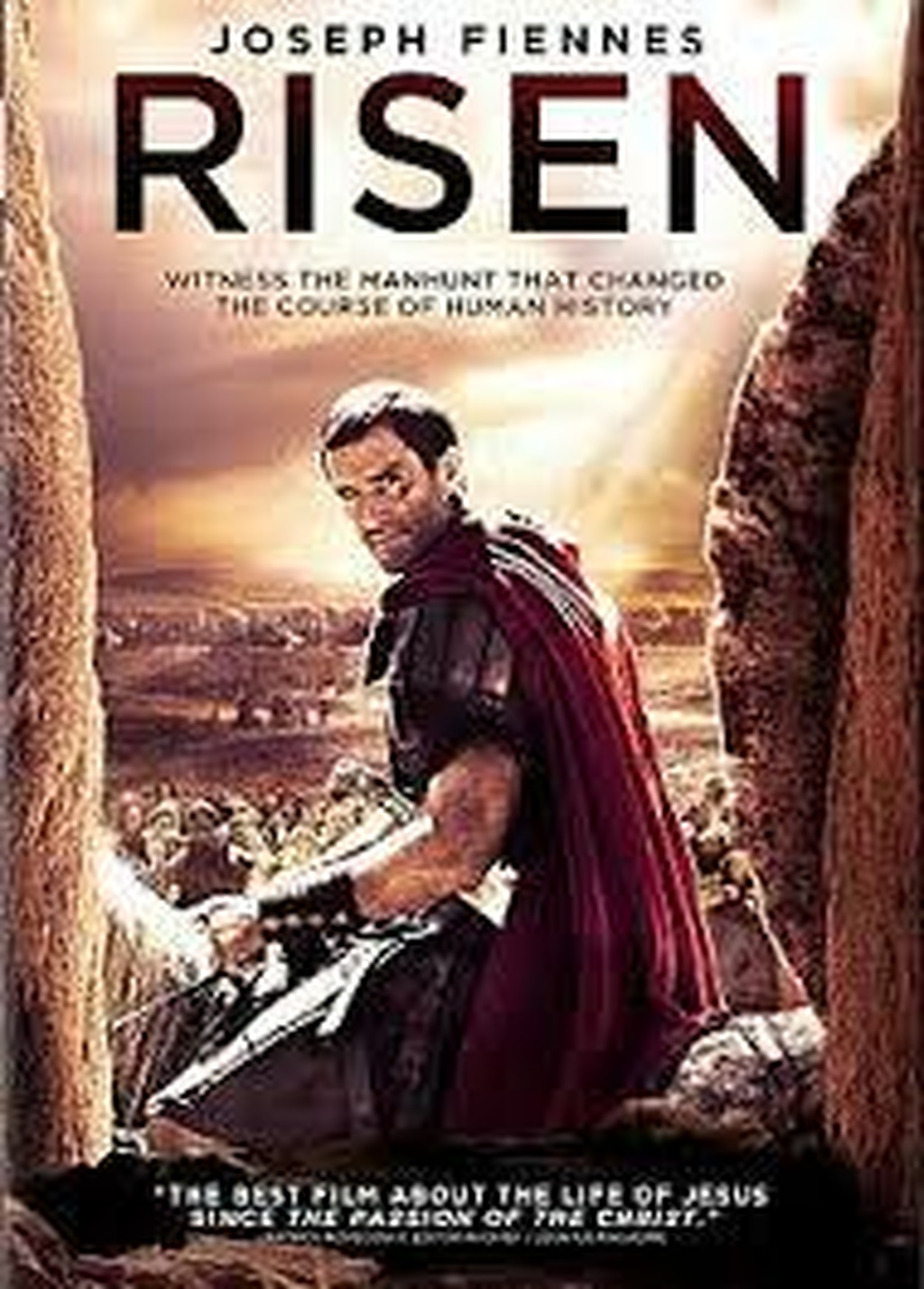

Risen is an old-fashioned “Bible movie” along the lines of The Robe or Ben-Hur—only it goes a bit farther than they did. Quite a bit farther; and it does a very good job of taking us along with it.

Joseph Fiennes plays Clavius, an intense, driven man inescapably haunted by the things he’s had to do as a soldier in a not very thoroughly pacified Roman province. Indeed, his first assignment under the new governor, Pontius Pilate (Peter Frith), is to break the crucified Jesus’ legs, to hasten death. But by then Jesus is already dead, and that should have been the end of it.

On the other side of the coin, Risen also gives us a rather chilling hint of what it’s like to live in a place ruled by aliens who can do anything they please to you, with no consequences to themselves. First-century Jews and Christians lived with that reality. So does Clavius: and it has wounded his soul.

Present at the Resurrection

There are a few minutes in this movie that take it to a whole new level. If this one scene were all there was to the film, it would be enough to reward your time spent watching it.

Jesus Christ has risen from the dead. Pilate, naturally, doesn’t believe that. When Clavius suggests, “Perhaps it’s true,” Pilate answers, “If it is, I’ll kill him again.” Believing that Jesus’ disciples have stolen the body, Pilate assigns Clavius to track them down and make them tell the truth. Pilate thinks Jesus’ followers somehow drugged the Roman guards—who were, after all, drinking wine throughout the night—at the tomb so they could remove the body.

In a seedy little tavern, Clavius catches up to one of the guards. The man is drinking as if his life depended on it, but he’s not yet too far gone to answer questions—only drunk enough to let his need to talk outweigh his very real fear of being put to death. It’s a small role, played by Richard Atwill, but it has enormous impact.

This is what the guard tells Clavius:

“We was wakened by this terrible flash … all of a sudden. The sun rose in the tomb! … A figure appeared, and we could not look on him. It wasn’t a man.”

You have to see it and hear it. You have to see Atwill’s face and look into his eyes. This man was there. He saw the resurrection. And he’s not lying about what he saw: he’s much too drunk, and much too terrified, to lie. This was the fulcrum of all human history, the turning-point of everything: and this man saw it.

You won’t see many performances as unforgettable as this one. The tomb of Jesus Christ has burst open, and everything has changed.

On the Trail of Jesus

What is Clavius to make of this? He’s a pagan, and so marred by his own experiences in life that he can hardly believe in anything. He has witnessed the horror of the crucifixion. He has searched among a heap of decaying corpses for the body of this man whom Pilate killed. Those scenes are rather graphic, and quite convincing, too. The film is rated PG-13 for “Biblical violence including some disturbing images.”1 Well, they’re disturbing, all right: but how else are we to understand the magnitude of evil, of human fallenness, that Christ has overcome?

Clavius continues on his quest, a mission which is changing him even as he pursues it, drawing him away from the Roman life that was all he knew, and all he had. Christ will do that to you. We are reminded of the spiritual journey of Paul, from hate-filled persecutor of the church to Apostle to the Gentiles.

“This threatens them, Caiaphas and Rome,” says Clavius. It also threatens the man he used to be, but by now he’s too deeply involved even to notice that.

Eventually he finds the disciples, talks with them, eats with them—even saves them from a Roman posse: an incident which is not in the Bible and which the movie would have been better off without. But the disciples can’t tell him what he wants to know. “We’re astounded, too,” admits Peter (Stewart Scudamore).

Finally he meets Jesus (Cliff Curtis), the Risen Christ. Clavius says, “I don’t even know what to ask … I cannot reconcile this with the world I know.”

And at the end he is asked, “Tribune, do you truly believe all this?”

To which he answers, “I believe. I can never be the same.”

A Pitfall to Avoid

In John 20:25, Thomas says, “Except I shall see in his hands the print of the nails, and put my finger into the print of the nails, and thrust my hand into his side, I will not believe.”

Eight days later, Thomas sees the risen Jesus, sees the wounds, and believes. And Jesus says, “Thomas, because thou hast seen me, thou hast believed: blessed are they that have not seen, and yet have believed” (John 20:29).

Here is the trap that most Bible movies fall into—showing us too much, making it too easy for us. Risen falls into it, too.

How can Clavius not believe, after all he’s seen? Like Thomas, he’s seen everything. He was even present at the ascension.

But where does that leave us? We didn’t see Jesus nailed to the cross and taken down, dead. We never had the opportunity to see Him afterward, alive—to see Him in the flesh, and talk with Him face-to-face. We have to believe, somehow, without having seen.

Risen could have attained greatness if Clavius had never seen Jesus alive after he was dead, had never received the same kind of proofs that Thomas had—if he had wound up in the same boat with the rest of us and still, by the sovereign grace of God, received the gift of faith. Then it would have been a powerful story indeed, and I suspect Joseph Fiennes would have loved the challenge of performing it.

Bible movies can only take us so far, and never far enough. We who cannot see Jesus in the flesh, until the restoration of all things, need very much more than what our eyes and ears can tell us. We need the faith that only God can give us.

Paul wrote, “For we are saved by hope: but hope that is seen is not hope: for what a man seeth, why doth he yet hope for? But if we hope for that we see not, then do we with patience wait for it” (Rom. 8:24–25).

On these very important counts, Risen comes up short.

But thanks to a few minutes on the screen by Robert Atwill, it’s still a movie that will be good for you to see.

1. I have no idea why there should be a special category for “Biblical violence,” nor can I explain how it differs from non-Biblical violence, whatever that may be.

- Lee Duigon

Lee is the author of the Bell Mountain Series of novels and a contributing editor for our Faith for All of Life magazine. Lee provides commentary on cultural trends and relevant issues to Christians, along with providing cogent book and media reviews.

Lee has his own blog at www.leeduigon.com.