"When You Hear the Bell, Come Out Writing"

Fantasy is important, and not just because of its popularity. Because it’s so closely tied to the imagination, both the writer’s and the reader’s, it has access to regions of the mind that are not easily reached by other kinds of fiction. In this it resembles poetry.

- Lee Duigon

It started with a dream.

I dreamed I was standing in a grassy meadow by a river, looking up at looming mountains. They were really rather far away, but they looked close enough to reach out and touch.

And then, I didn’t know why, from the summit of the tallest mountain came the sound of bells. Beautiful, but also, in some way, frightening. So much so, it woke me up.

And that was the opening scene of my first novel for Chalcedon, Bell Mountain, dreamed of in 2008, published in 2010, and with a young boy named Jack standing in my place, and in a world of my imagination.

At about the same time, providentially, someone at Chalcedon wondered, “Why don’t we have a try at publishing a novel?” And our managing editor, Susan Burns, remembered that we already had a published novelist writing for Chalcedon. Me.

Could I do it?

I certainly wanted to try.

A Christian Fantasy Novel

From early childhood the only thing I truly wanted to be, when I grew up, was a story-teller. A writer. I wrote scary stories for my friends. In middle school I wrote a science fiction novel. In high school I discovered fantasy—Edgar Rice Burroughs, then J.R.R. Tolkien—and I was firmly hooked: I wanted to write fantasy. The Lord of the Rings totally blew me away. I had to write something like that!

Then followed several decades of trying. In the 1980s I began to sell short stories, most of them to Mike Shayne’s Mystery Magazine. And in 1988 I sold my first horror novel, Lifeblood, followed by three more—until the horror market imploded and left me high and dry.

Not that it ever occurred to me to question it, not that I was even aware, at the time, that this was a problem—but all that writing, stacks and stacks of it, was for me. I wanted to be famous. I wanted to be rich. I should have remembered the words of the Psalm: “Except the Lord build the house, they labor in vain that build it” (Ps. 127:1). This house was for me, and I labored on it in vain. Very little came of it.

But unexpectedly, twenty years after Lifeblood, I had the opportunity to try again. My colleagues at Chalcedon were giving me a chance.

And all I knew was that this time, it would have to be different. Everything would have to be different. This book would not be written for my own aggrandizement. This would have to be in the service of Christ’s Kingdom. When I look back on it, I marvel that I dared to go ahead with such a work.

Taking the dream of the mountain as my starting-point, I jumped right in.

Christian fantasy was not a new idea. C.S. Lewis’ The Chronicles of Narnia, and Tolkien’s works, towered over the field and had attracted millions of readers over the years. The Harry Potter books were selling like mad (I do not agree with those who see them as Christian fantasy, but let that be for now). Fantasy had long been a big market, especially for young adult readers.

But so much of fantasy was lame, unoriginal, heavy on the sex and violence, steeped in the occult, and not to be recommended to young Christian readers. We couldn’t justify serving up more of the same. Bell Mountain (I had the title early on) would have to be compatible with Christian teachings, conformable to God’s word in the Bible, and as far removed as possible from the clichés and conventions of worldly fantasy.

Fantasy is important, and not just because of its popularity. Because it’s so closely tied to the imagination, both the writer’s and the reader’s, it has access to regions of the mind that are not easily reached by other kinds of fiction. In this it resembles poetry.

Eleven Books So Far

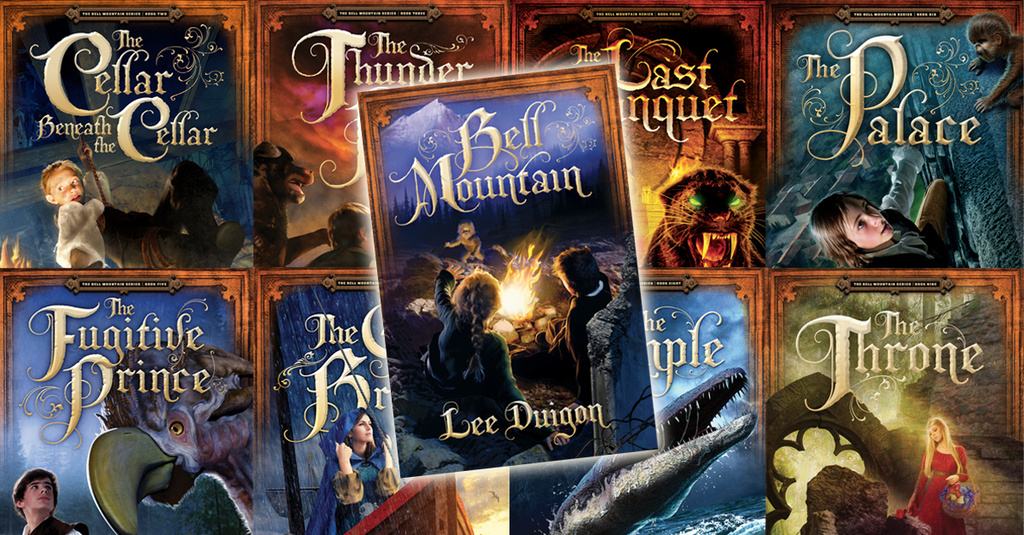

We have now ten Bell Mountain books in print, with No. 11, The Temptation, on the verge of being published. In the time I’ve spent writing them, I’ve learned something that I hadn’t realized earlier.

All fiction is a form of entertainment, along with movies, television, comic books, etc.—and people consume entertainment in prodigious quantities. They consume it to relax, to escape from daily cares, to occupy their minds: and in so doing, they passively self-educate. Very few of them are aware they’re doing this: it’s this “passive” part that makes the “education” so effective. The reader’s or the movie viewer’s barriers are down. Because it’s “only entertainment,” the content of the entertainment usually gets through the gate unchallenged.

That makes it very effective indeed. To what extent is our whole outlook on life influenced by the hundreds or even thousands of hours we spend, lifelong, passively consuming entertainment? Hint: if the answer were “not at all,” no one would produce commercials.

In writing Bell Mountain and its sequels, I made some decisions which have served me well.

First, I ruled out magic. There would be no magic, no wizards, no magical items, no spells, no super powers in my books. There would be no contravening the observable laws of nature that God has built into the world. The characters in the stories might think they’re seeing something magical, but they would be mistaken.

Second, I would allow in my imaginary world only whatever the Bible allows in ours. That’s not as restrictive as it sounds. Answered prayers, miracles, fulfillment of scriptural prophecies, heroism and villainy, narrow escapes, great deliverances—everything that’s really in our world can be found in the Bible. What more reliable guide could I have?

And third, since I was writing of an imaginary world that’s not our world, it would have to follow its own unique arc of history, different from our own. This allowed me to posit an advanced civilization, destroyed a thousand years ago, with a quasi-medieval civilization succeeding it. I switched the modern ages and the Middle Ages. We’ve had a lot of fun with that.

I have also tried very hard to make my characters, all of them, believable. I’ve read any number of young readers’ fantasy novels in which children are given preposterous abilities. Really, I don’t care how much kung fu a ten-year-old girl has studied. She is not going to whale the living daylights out of a grown man. This kind of nonsense is all too common in today’s fantasy literature. It goes hand in glove with the author endowing characters with magical skills and super powers. It’s not wholesome stuff to be feeding young readers.

I have included creatures in my imaginary world which may seem fantastic; but however unusual they are, they still conform to the laws of God’s creation. If Ellayne in my world of Obann were reading a fantasy about our world (to her, it would be a fantasy), she might find a Shetland pony or a giant panda a little hard to imagine. And a suburban township might strike her as impossible.

Relying on God

Another thing I decided to do differently: instead of planning out the whole story in detail before I started writing it, now I say a prayer to ask for guidance and just go ahead.

When I wrote a horror novel, I filled spiral notebooks with biographies of all the characters and wrote each incident of the plot onto an index card—and color-coded the cards for the various subplots, so I could spread them out in front of me and move them around until I decided on the best placement of each incident. It took me six months to prepare a book. I wouldn’t type a word of it until I’d laid all the groundwork.

I’d like to say this made the books turn out perfect, but it didn’t.

Trusting in God’s guidance and just plunging into it has rewarded me with some unusual experiences. I often don’t know, from one day to the next, just what I’m going to write, just where the story’s going to go. Sometimes minor characters grow into major characters. Sometimes things happen to the characters that profoundly change them; and then they change the plot.

Lord Orth, for instance, started as a corrupt churchman and a second-fiddle villain, experienced the total ruin of all his master’s plans, temporarily lost his mind, and has since gone on to play a major role in the sequels—and I don’t want to spoil it for potential readers by saying what that role is. It certainly isn’t anything at all like I expected, when I first introduced him into the story. I have to admit none of it was planned.

As I tried to write a climax for No. 5, The Fugitive Prince, I knew I was approaching the climax, but had no idea what it would be. I put away my legal pad at the end of the day and walked a few blocks, just a few, to pick up our dinner at our local Chinese restaurant. And by the time I got there, I had the whole blessed thing! Three chapters’ worth—and to me, at least, a total surprise.

Dreams gave me the climax of No. 3, The Thunder King, and the beginning of No. 4, The Last Banquet. For my birthday, two years ago, I received about half the plot of No. 9, The Throne. The thing is, if I wait, I get these books in flashes. If I try to dope the stories out, intellectually, I get nothing. And yet when I read the finished product, the story always holds together: it shows no sign of being unplanned.

The books are a lot smarter than I am, and I give God the glory for that.

World Without End

I’m often asked how many Bell Mountain books I mean to write; and the only answer I can make is, “However many God gives me.”

The stories, after all, are part of a history, and the world of Obann is very far from its history coming to an end. To make a Biblical analogy, that world is still in the Old Testament, with just the first glimmers of a New Testament beginning to peek through.

I’m always delighted and surprised when readers tell me how much they and their children have enjoyed these books. I’m especially surprised when it’s very young children, as young as five. I write with an audience of twelve-year-olds in mind, taking care not to lose adult readers along the way; and I also bear it in mind that it takes time to read the books, and that many of the readers will themselves be growing up as they read: so it’s important to me not to write down to them.

Some have responded to these books with deep emotion, but that’s between me and them. When I started, I never expected that anything I wrote would have spiritual significance for anyone. Suffice it to say I was wrong about that.

Sometimes I’m tempted to go back into Obann’s past, long past, and write of King Ozias, the last anointed king, who wrote the Sacred Songs and erected the bell on top of Bell Mountain. Or back to the great days of Obann’s Empire, a civilization as technologically advanced—and as spiritually backward—as our own twentieth century. But then I remember that the young characters I’ve been writing about all along—Jack and Ellayne, who rang the bell; Ryons, the slave-boy who became a king; Jandra, the little girl chosen by God to be a prophet; Gurun from the cold northern isles, swept away by a storm to become the Queen of Obann; and Wytt, not human, squirrel-sized, appointed by the Lord to protect the children: he’s a lot of readers’ favorite character.

I would love to tell you how two minor characters stepped forth to wrap up the climax of No. 12, His Mercy Endureth Forever, but I don’t want to risk spoiling the story for you.

Get the entire Bell Mountain Series. Click now to learn more!L

- Lee Duigon

Lee is the author of the Bell Mountain Series of novels and a contributing editor for our Faith for All of Life magazine. Lee provides commentary on cultural trends and relevant issues to Christians, along with providing cogent book and media reviews.

Lee has his own blog at www.leeduigon.com.